CLICK HERE FOR ITALIAN VERSION

Laura Arias Serrano

Las fuentes de la historia del arte en la época contemporánea [The sources of art history in the contemporary era]

Barcelona, Ediciones del Serbal, S.A, 2012, 759 pages

Review by Francesco Mazzaferro. Part Two

Las fuentes de la historia del arte en la época contemporánea [The sources of art history in the contemporary era]

Barcelona, Ediciones del Serbal, S.A, 2012, 759 pages

Review by Francesco Mazzaferro. Part Two

|

| Fig. 7) Laura Arias Serrano’s reasoned bibliography after an intense reading |

Go Back to Part One

The sources in their historical context

The second part of Laura Arias

Serrano's work on the sources of art history in the contemporary era, spreading

over five hundred pages, offers a very rich, reasoned bibliography, structured

according to the type of source and, within any of them, in chronological

order. The analysed period goes from the beginning of the XVIII century to the

end of the XX century.

It is obviously impossible here to

discuss the content of the specific reviews which the authoress wrote on the different works. Instead, I

would like to try to identify the common narrative, focusing on those texts

which - according to the authoress - are the indispensable stages in the

history of artistic literature during the last three hundred years, genre by

genre. As mentioned in the first part, Laura Arias Serrano has always cited the

works in their most recent edition: the bibliography therefore allows us to

understand which have been released recently and which works, on the contrary, have not been for some

time. In some cases, the writings are available on electronic archives and

therefore easy to consult; in others we have only facsimile editions, which

therefore reproduce the texts without updated comments.

A systematic comparison between the

works available in Spanish and other languages (in particular French and

Italian) reveals one of the reasons that may have perhaps prompted Laura Arias

Serrano to draw up such a powerful bibliographic work: to remedy a relative

scarcity of modern editions available on the Hispanic market and to offer a

precise idea to Spanish scholars of what they can consult in a particularly

equipped library, using rare editions (often many decades old, and in many

cases due to the activity of publishing houses in Latin America). Since

Spanish-speaking publishing was not enough, the authoress also reported what can

also be read in English, French or Italian. The references are limited to these

four idioms (German is excluded, for example).

I will focus on the first two

chapters: (i) treatises, aesthetics and historiography texts, encyclopaedias

and dictionaries and (ii) theoretical texts by the artists.

Treatises. Aesthetic and historiography texts. Encyclopedias and

dictionaries

In this first section the authoress

took into consideration those theoretical texts on art, which are not written

by artists (those by artists are in fact considered separately, although, to be honest,

the section also includes works by theorists who were well-known artists, like

Flaxman, Füssli, Reynolds and von Hildebrand). The history of these writings,

beyond the aesthetic theme, is in many cases also the expression of the general

culture of an era.

The forms these texts have taken

over the three hundred years vary considerably.

In the XVIII century, the 'classic'

form of the treaty was still prevailing [38]. In the middle of that century, in

fact, “the word «source» itself is synonymous with treatise,

in the same way in which the conception of art is always associated with an

activity specifically dedicated to the selective imitation of reality in an

attempt to reach beauty” [39]. Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten's (1714-1762) Aesthetics (1750-1758), reviewed here in the 2000

Italian edition [40], and the History of

the art of antiquity (1764) by Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-1768), in a Spanish version

of 1989 [41], were the two reference treatises on the theme of beauty in the

German world. The first attempt at art history was the Thoughts on the imitation of Greek art in painting and sculpture

(1755) by Winckelmann himself, reviewed in the Spanish edition of 1987 [42],

and the History of sculpture from its

resurgence in Italy up to the century of Canova (1823) by Leopoldo Cicognara (1767-1834), without Spanish

translation to date, cited in the Giachetti edition of 1823 [43]. As to France,

the authoress reviewed two works by Antoine Quatremère de Quincy (1755-1849): the Moral considerations on the destination of

the works of art (1832), in a recent French edition [44] and the Study on the nature, purpose and means of

imitation in the fine arts (1823) in a Belgian facsimile edition of 1980

[45]. As to Spain, the authoress wrote on one of the many works by Juan

Agustín Ceán-Bermúdez

(1749-1829), or the Sumario de las

antigüedades romanas que hay en España, dated 1832 and consulted in a

facsimile edition of 2003 [46].

Also as a result of the

Enlightenment and in the wake of the Encyclopédie

(1751-1772) by Denis Diderot (1713-1784) and Jean-Baptiste Le Rond

d'Alembert (1717-1783) - here reviewed in the edition of Franco Maria Ricci in

18 volumes of 1970-1979 [47] - attempts to give a systematic set-up to knowledge were

multiplying. In the French world the role of the already mentioned Quatremère

de Quincy and then Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc (1814-1879) stands out, thanks

to the reasoned dictionaries of the history of architecture, written

respectively with a neoclassical inspiration in the first case, and with a neo-gothic

one in the second. In the first case, it was the Dictionnaire historique d'architecture (1832), whose items on

theory were published in Spanish in Buenos Aires in 2003 [48]. In the second

case, they were the Dictionnaire raisonné

de l'architecture française du xi au xvi siècle (1854-1868) [49] in 10

volumes, and the Dictionnaire raisonné du

mobilier français de l'époque carolingienne à la Renaissance in 6 volumes

(1858-1870), both reviewed in facsimile editions of the second half of the

twentieth century [50].

In the Spanish world the fashion of

reasoned dictionaries spread in 1788 with two works. The first was the Introducción al conocimiento de las Bellas

Artes, ó Diccionario manual de Pintura, Escultura, Arquitectura, Grabado, the

work of father Francisco Martínez (1736-1794), cited in a facsimile edition of

1989 [51]. The second was the

Diccionario de las nobles artes para

instrucción de los aficionados, y uso de los profesores by Diego Antonio

Rejón de Silva (1754-1796), of which the authoress reported a facsmile edition

of 1989 [52]. A few

decades later, it was time for bibliographic dictionaries, with works by

Eugenio de Llaguno y Amírola (1724-1799) [53] and the aforementioned

Ceán-Bermúdez [54] - the latter continued by the Count de la Viñaza (1862-1933)

[55]. More recent were the bibliographic dictionaries by Manuel Ossorio y

Bernard [56] (1839-1904) and José Ruiz de Lihory y Pardines [57] (1852-1920),

dated 1883 and 1897 respectively. In the latter case there is no recent edition

[58].

Alongside the neoclassical vulgate,

new sensibilities spread in the XVIII century starting from Great Britain. A

new typology of artistic literature was also being born, which no longer aimed

at having a systematic nature, but rather at corroborating a thesis: treatises

or reasoned dictionaries were replaced by speeches and essays. The authoress

referred first of all to the Pleasures of

the imagination (1712) by Joseph Addison (1672-1719), a work she took into

consideration in a Spanish edition of 1991 [59]. Edmund Burke (1729-1797) and William Gilpin

(1724-1804) follow. Laura Arias Serrano reviewed Burke's Inquiry into the beautiful and the sublime (1757) [60] in a 1985 Spanish edition. Gilpin was present with the Three essays on picturesque beauty

(1794), translated into Spanish in 2004 [61] (there is no Italian edition). As to

the Discourses on Art by Joshua Reynolds (1723-1792), only an Argentine

edition of 1943 is mentioned [62], even if a Spanish one was published in 2005

[63]. The Discourses on Sculpture by

John Flaxman (1755-1826), cited in the nineteenth-century English edition,

belong to the new suggestions produced in the English world of the nineteenth

century [64] (there were no modern editions neither in Spanish nor in Italian

[65]). The same cultural climate applies to the Lectures on painting by Johann Heinrich Füssli (1741-1825) in the French edition

of 1994 (they were recently reissued in 2017) [66]. There is no complete modern

edition in the English original [67]. Laura Arias Serrano obviously also took

note of the contributions to the aesthetic philosophy of Jean-Jacques Rousseau

(1712-1778) and Immanuel Kant (1724-1804).

At the University of Jena, the

German world developed an aesthetic theory of romanticism strongly

characterized by idealistic historicism. Wilhelm Heinrich Wackenroder

(1773-1798) and Ludwig Tieck (1773-1853) published in 1797 the Outpourings from the Heart of an Art-loving

Monk, which marked a real revolution in taste in Germany. The work was

reviewed in a Spanish version of 2008 [68]; I would also like to point out a

more recent Italian translation [69]. To these were added the major theoretical

texts of aesthetics by Friedrich Schiller (1759-1805), Georg Wilhelm

Friedrich Hegel (1770-1831), Friedrich Schelling (1775-1854) and Friedrich

Schlegel (1772-1829).

At the turn of the nineteenth and

twentieth centuries, the treatises were replaced by theoretical texts of

aesthetic and historiographic orientation, which were the reflection of the

irruption of new currents of thought - think of Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) - and of new disciplines, such as example psychology [70]. The new

approaches to studying art would help create the foundations of modernism. The

Vienna school is present with Problems of

style: foundations of a history of ornamental art (1893) by Alois Riegl

(1858-1905), reviewed in a Spanish translation of 1980 [71] (the most recent

Italian edition was from 1963 [72]). As to abstraction theory, the bibliography

includes Wilhelm Worringer's (1881-1965) Abstraction

and Empathy (1908) in a 1983 Mexican edition [73] (there was a

reprint in 2015; the most recent Italian edition was from 2008 [74]). It should

be noted that the Mexican interest in the work was not occasional: it has been

reprinted six times in Mexico City since the fifties by Mariana Frenk Westheim

(1898-2004), scholar of literature and art and wife of Paul Westheim, one of the protagonists of the modernist

culture of the Weimar Republic (the couple flied to Mexico at the arrival of

Nazism).

The formalist school is present with

Adolf von Hildebrand (1847-1921) and Konrad Fiedler (1841-1895). The former was

included with The Problem of Form in

Painting and Sculpture (1893), in a Spanish translation of 1989 [75] (in

Italy the last edition was dated 2001 [76]). As to the second, two works are

presented: The Writings on Art (1896)

in a Madrid translation of 1992 [77] and On

the essence of art (1914) in the Argentinian edition of the 1950s [78] (the

last Italian edition of his Writings was dated 2006 [79]). The Argentinian edition was curated by Hans Eckstein (1898-1985), whose anthology of

artistic literature in the versions of 1938 and 1954 we have reviewed in this

blog.

|

| Fig. 14) The Dehumanization of Art by José Ortega y Gasset. Above: Spanish versions from 1960, 2007, 2009, 2015 and 2016. Below, Italian versions from 2005, 2010 and 2016. |

The important contribution of

Spanish artists to modernism is testified by a philosopher and two leading

literates. The first is José Ortega y Gasset (1883-1955), with his The Dehumanization of Art (1925),

reviewed in his tenth Spanish reprint of 1996 [80] (in the meantime, the latest

edition is from 2009). It was one of the first texts, which tried to interpret,

in philosophical terms, the choice of abstract artists to break with the

classic definition of art as an imitation of nature. His unbroken editorial

fortune in many languages (including Italian) shows that the text is still

considered as a fundamental testimony of the aesthetic debate in the 1920s. On

the literature side the authoress added Guillelmo de Torre (1900-1971) with European avant-garde literatures (1925)

[81] and Ramón Gómez de la Serna Puig (1888-1963), with Ismos (1931) [82]. The former was a very young writer and literary

critic, exponent of the poetic-literary-artistic movement of Ultraism, and representative of the

dialogue of the Spanish avant-garde with France and Italy. The second - a poet

who invented the new aphoristic-conceptual genre of greguería - was close to many Spanish and non-Spanish modernist

artists, from Picasso to Delaunay, from Léger to Diego Riveira. The cited works

have not yet been translated into Italian or English. Instead they belong to

the classics of Spanish literature; they were reviewed in editions of 2001 [83]

and of 2002 [84] respectively.

Since the mid-twentieth century, the

multiplication of ideas and perspectives has led to an increasingly varied

debate and more and more to the use of periodical publications, designed to

inform the public about the continuous development of new ideas and their

comparison [85]. And this is where the section on theoretical texts stops. The

only work cited is Umberto Eco's The open

work. Form and indeterminacy in contemporary poetics (1962), considered a

fundamental book to understand the transition to an art that can increasingly

be interpreted in different directions. The work was reviewed in a Spanish edition

of 1990 [86].

In conclusion, I would like to note

three aspects of the fortune of the texts cited in the Spanish-speaking world:

firstly, the treatises of the XVIII century were often made available only in a

facsimile edition, without modern comments; secondly, since the 1940s and 1950s

the role of Latin American publishers in the dissemination of the most

significant aesthetic texts (Reynolds, Worringer, Fiedler) has been anything

but marginal; finally, the role of some specialized publishing houses was instrumental

to spread art literature in Spanish. In particular, the Madrid-based Visor presented to the Spanish public

the works of Addison, Fiedler, Hildebrand, Reynolds with the two series Discurso Artístico (Discourse on art) and

La Balsa de la Medusa (The raft of

the jellyfish).

Theoretical texts of the artists

According to Laura Arias Serrano,

theoretical texts written by artists themselves are undoubtedly the category of sources “which we consider most important” [87] and also the one where the

spectrum of the reasoned bibliography is wider. In a roundup of 150 pages, it

starts with the Reflections on Beauty and

Taste in Painting (1762) by Anton Raphael Mengs (1728-1779) and ends with

The Philosophy of Andy Warhol: From A to

B and Back Again (1975) by Andy Warhol (1928-1987).

The XVIII-century artists, as the

authoress wrote, not only manifested their personal preferences, but also those

of the circles in which they were firmly anchored: the academies (more related

to political power), secret societies and masonry (alternatives to monarchs and

principalities) or, again, the art market as an expression of a developing

civil society. Studying the artistic literature of this period, therefore, has above all the goal to draw "key

information on the artist's relations with society, on his training and on the

intellectual profile that artistic practice is taking on, completely separate

from pure artisan practice” [88].

The section opens - as it has been

said - with an author tightly linked to the Spanish world, i.e. Mengs. Laura

Arias Serrano reviewed his Reflections on

Beauty and Taste in Painting of 1762 in the facsimile edition of the first

Spanish translation of 1780, edited by José Nicolás de Azara (1730-1804). The

facsimile edition was published in 1989 [89] by the Dirección General de Bellas Artes y Archivos in Madrid, with an

introduction specially written for the occasion by Mercedes Aguedas Villar. In

Italian we have two versions, edited by Giuseppe Faggin (1948 [90], reprinted in 2003 [91]) and Michele Cometa (1996) [92] respectively.

In addition to the aforementioned

Reynolds (there are some evident repetitions between the two chapters), Mengs’s

works were also joined by the Reflections

on sculpture (1762) by Étienne Maurice Falconet (1716-1791) and The Analysis of Beauty (1752) by William Hogarth (1697-1764). Only a partial

edition of Falconet is available in Spanish, thanks to an anthology of sources

of baroque art history dated 1983 [93] (while the full text has just been published in Italian [94]). Hogarth's

writing was reviewed in a version printed by the publishing house Visor in

1997 [95].

The arrival of romanticism affirmed

the idea of the artist as a man of genius. His artistic expression was seen as the

result of an exclusively intimate experience; it followed that his writings were

a unique and revealing expression of his works. The artist "writes with much greater force, explaining

how he can and where he can his thoughts, his yearnings, his concerns”

[96]. Academic thought and criticism were therefore contested by artists as

reliable sources of reading their work. The writings of the artists became

shorter and less systematic, while the publication of the correspondence was

affirmed, as an authentic testimony of a way of thinking.

The nineteenth century opened with

the contrast between Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867) and Eugène

Delacroix (1798-1863). The complete collection of Ingres' writings, in two

volumes, came out in 1947-1948 with the title Ingres: Raconté par Lui-Même et par ses amis: Pensées et Ecrits du

Peintre [97], as part of a Swiss-French series of memories of great artists (such as

Manet, Van Gogh, Courbet, Corot), always seen by themselves and by friends. The

first volume largely presented the artist's unpublished papers, while in the

second the testimonies of friends prevailed. There was no Spanish edition of

the painter's writings, while Elena Pontiggia published Ingres' Thoughts on the art in Italian in 2003

in the Carte d'Artisti series; Laura

Arias Serrano also dedicated a separate review to Ms Pontiggia's introductory text [98].

The writings of Delacroix, if

compared to those of Ingres, had a much greater fortune. In the French world

Delacroix was considered, for the style of writing, the master of

nineteenth-century artistic literature (it is famous the edition edited by A.

Joubin, to which Laura Arias Serrano also referred) [99]. As to Spain, the

authoress reviewed an anthology of the Journal

of 1998, recently reissued in 2011 in an enlarged version [100]. It is a

selection that presents about a quarter of the diaries; the chosen pages are

concentrated on themes of style and artistic theory (excluding biographical

episodes). A larger (but incomplete) version had been published in Spanish in

Mexico City in 1946 [101]. As for Italy, this blog reviews the Einaudi version in 3 volumes, dated

1954 and edited by Lamberto Vitali [102]. The most recent Italian edition was brought out 2017 [103]

(however, it was a reprint of the translation made by the writer Lalla Romano

in 1946 [104]).

Among the landscape painters, Laura

Arias Serrano reviewed a set of writings by and on Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot

(1796-1875), entitled Corot raconté par

lui même et par ses amis (1946) [105], published in the aforementioned

collection of Swiss-French art literature of the 1940s. There were no more

recent editions, neither in French nor in Spanish or in Italian. The English

edition of John Constable's Discourses (1836)

(1776-1837) [106], published by the Suffolk Records Society, dated back to 1970.

It should be added that, in addition to the Discourses

(the only volume cited by the author), the same society published the

complete correspondence of the painter in six volumes in the 1960s [107]; two

further volumes were added in 1975 in cooperation with the Tate Gallery [108].

There were no Spanish or Italian editions.

|

| Fig. 20) On the left, the important edition of John Constable's writings by the Suffolk Records Society. From left to right, the Discourses and some volumes of correspondence. |

Madrid's Visor publisher edited an

anthology of Letters and note on

landscape painting (1831) by Carl Gustav Carus (1789-1869) [109], also

documenting his friendship relationship with Goethe. In Italian, editions came out in 1991 and

2002 by Edizioni Studio Tesi of Pordenone. Finally, the authoress also reviewed

a fragment by Caspar David Friedrich (1774-1840) on The inner voice (1820), taken from a Spanish anthology of

romantic sources on art [110]. There were many editions in German, including a

full critical edition of Friedrich's texts (started, but not yet completed, in

1999) [111]; in Italian, a collection of writings by the German painter was

published by Abscondita in 2001 by Luisa Rubini (with reprint in 2017) [112].

Laura Arias Serrano presented Nazarenes and Pre-Raphaelites in parallel, referring to Johann Friedrich

Overbeck (1789-1869) and John Ruskin (1819-1900). Overbeck's script was drawn from a famous American anthology

about art art literature, published by Prentice Hall [113], in the absence of Spanish

publications. The complete publication of the letters and texts of the Nazarene

painter in German also dated back to the nineteenth century [114] and I have

found no evidence of more recent versions. Ruskin's huge written production is

represented here by a Spanish translation [115] of 1906 of Pre-Raphaelitism: Lectures on Architecture and Painting. To tell

the truth, a recent reprint of the same volume (2014) was published in Pamplona

[116]. Furthermore, this is certainly not Ruskin's only work in Spanish, and

many other works of his have been printed, even recently. Several of them are

mentioned in other sections of the volume: all in all, the main concern of the

authoress - including the non-artist Ruskin also in the chapter of artists' texts - must have been the absence on the Spanish market of translated texts by

pre-Raphaelite artists.

The nineteenth-century realism is

testified by the review of the manifesto that Gustav Courbet (1819-1877)

attached to the catalogue of the 1855 realist exhibition. He organized that

show in protest after the refusal of the direction of the Universal Exposition

to exhibit his works. The authoress showed marked interest in the manifesto,

using a 1969 Italian edition of an essay by the French art critic Georges

Boudaille [117]. There were several versions of the Courbet manifesto: a

different version, which appeared in 1950 in the collection of writings Courbet raconté par lui-même et par ses amis

(1950), was published in the aforementioned collection of Franco-Swiss artistic

literature of the publisher Pierre Cailler [118]. Courbet's political texts were defended in

particular by the philosopher Pierre Joseph Proudhon (1809-1865) in his

posthumous work Du principe de l'art e de

sa destination sociale (1871) [119], a text which was a best-seller in the Hispanic world

(with editions in Peru in the nineteenth century [120] and then in Argentina in

the twentieth century [121]), but has not yet been printed in Italy.

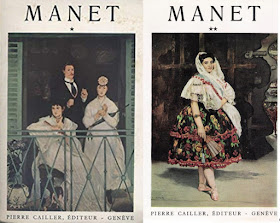

Significantly, the reasoned

bibliography does not include impressionist artists. According to the authoress,

in fact, no painters of this orientation have left written testimonies worthy

of mention. Interestingly, she did not include in her bibliography the two volumes of writings, Manet raconté par lui-même et ses amis, published in the Swiss-French series in 1945 in the usual two-volume structure (the first with texts by the artist, the

second with the testimonies of friends) [122].

Post-Impressionism opens with the

works of Georges Seurat (1859-1891) and Paul Signac (1863-1935). As to the

former artist, a French anthology of writings was brought out in 1991 [123]; as

to second, the painter published the work From

Eugène Delacroix to neo-impressionism (1899), which he dedicated to Seurat.

Signac's essay was reviewed here in an Argentinian version of 1943, the only

one available in the Hispanic world [124]. The work is one of the most

fortunate artists' texts in the French world (about twenty reprints, the latest

in 2014); it is present in Italy with three editions between 1964 and 1993.

|

| Fig. 25) Two Spanish collections of writings by Paul Cézanne, deriving from diverging American editions, curated by Richard Kendall and John Rewald. |

The following section is devoted to Paul

Cézanne (1839-1906), Paul Gauguin (1848-1903) and Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890).

And here it must be said that the editorial success in the Spanish world has produced

an overlap of similar editions.

Cézanne's writings were reported in

two recent Spanish editions, 1989 and 1991 respectively. The first was the

Spanish translation [125] of Cézanne by

Himself: Drawings, Paintings, Writings, edited by art historian Richard

Kendall [126]. The second was the translation [127], published by Visor of

Madrid, of the edition [128] (1937) of Correspondence

by the American art historian John Rewald (1912-1994) [129]. We know well the vicissitudes of the

very successful Rewald edition, no longer considered reliable. To be noted, the recent new

critical edition by Alex Danchev [130] of 2013 is not yet available outside the

English-language book market. The Visor edition was the latest of the Spanish

versions of the collection edited by Rewald, which has appeared regularly,

albeit in different translations, starting from the Argentine translation of

1948 [131].

As to Gauguin, the bibliography

includes the anthological collection Escritos

de un salvaje - Writings of a savage (2000) by Miguel Morán Turina [132].

The work celebrated Gauguin as a savage, giving an opposite interpretation to

the rationalist one that Chipp provided in 1968. It was inspired, instead, by the French

anthology of Gauguin’s writings Oviri:

écrits d'un sauvage, published by Daniel Guérin in 1974 [133] and of which

there are two Spanish translations. The first was edited by Margarita Latorre

and brought out in 1975 and 1995. The second (2008) was by Marta

Sánchez-Eguibar [134]. So, despite the same Spanish title, three different

versions of Gauguin's writings have been published.

Vincent van Gogh's Letters to Theo were reviewed in a

paperback edition of 1985 with an introduction by the writer Mauro Armiño. In

truth there were many editions, starting from the 1970s (edited for example by

Fayad Jamís, Francisco de Oraa, Milagros Moleiro, Francisco-Luis Cardona

Castro, David García López, Antonio Rabinad, Víctor Goldstein and others). It

is therefore an 'inflated' text. Nevertheless, there is no complete Spanish

edition of all the letters so far.

End of Part Two

NOTES

[39] Arias Serrano, Laura - Las fuentes de la historia del arte en la época contemporánea (quoted), p.125.

[40] Baumgarten, Alexander Gottlieb - L'Estetica. Edited by Salvatore Tedesco; Palermo, Aesthetica, 2000, 368 pages.

[41] Winckelmann, Johann Joachim - Historia Del Arte En La Antigüedad. Seguida De Las Observaciones Sobre La Arquitectura De Los Antiguos. Con Un Estudio Crítico Por J.W. Goethe. Introducción Y Traducción Del Alemán Por Manuel Tamayo, Madrid, Aguilar, 1989, 606 pages.

[42] Winckelmann, Johann Joachim - Reflexiones sobre la imitación del arte griego en pintura y escultura. Edited by Ludwig Uhlig and Vicente Jarque, Barcelona Península, 1987, 163 pages.

[43] The work can be consulted at the address

https://archive.org/search.php?query=Storia%20Della%20Scultura%20Dal%20Suo%20Risorgimento%20in%20Italia%20Fino%20Al%20Secolo%20Di%20Canova.

[44] Quatremère de Quincy, Antoine - Considérations morales sur la destination des ouvrages de l'art. (suivi de) Lettres sur l'enlèvement des ouvrages de l'art antique à Athènes et à Rome, Paris, Fayard, 1989, 256 pagine. The moral considerations published in 1832 also include the famous letters to General Miranda, published as from 1796 in a series of newspapers.

[45] Quatremère de Quincy, Antoine - Essai sur la nature, le but et les moyens de l'imitation dans les beaux-arts, Archives d'Architecture Moderne, Bruxelles, 1980.

[46] Ceán Bermúdez, Juan Agustín - Sumario de las antigüedades romanas que hay en España, en especial las pertenecientes a las Bellas Artes, Valencia, Librería París-Valencia, 2003.

[47] Encyclopédie de Diderot et d'Alembert. Edited by Andrea Calzolari e Sylvie Delassus. Parma, Franco Maria Ricci editore, 1970-1979.

[48] Quatremère de Quincy, Antoine - Diccionario de arquitectura : voces teóricas. Edited by Fernando Aliata and Claudia Shmidt, Buenos Aires, Nobuko, 2007, 245 pages.

[49] Viollet-le-Duc, Emmanuel - Dictionnaire raisonné de l'architecture française du xi au xvi siècle, Parigi, F. de Nobele, 1967, 10 volumes.

[50] Viollet-le-Duc, Emmanuel - Dictionnaire raisonné du mobilier français de l'époque carolingienne à la Renaissance, Madrid, Asociación El Cid, Madrid, 1974, 6 volumes.

[51] Martínez, Francisco - Introducción al conocimiento de las Bellas Artes. Diccionario de Pintura, Arquitectura, escultura y Grabado, Colegio Oficial de Aparejadores y Arquitectos Técnicos. Introduction by Manuel Alvar Ezquerra, Madrid, 1989, 419 pages.

[52] Rejón de Silva, Diego Antonio - Diccionario de las nobles artes para instrucción de los aficionados, y uso de los profesores, Malaga, Fundación Cultural COAM, 1989, 217 pages.

[53] De Llaguno y Amírola, Eugenio - Noticias de los Arquitectos y Arquitectura de España desde su restauracion, Madrid, Turner, 1977, 4 volumes (facsimile version of the posthumous original of 1829).

[54] Ceán Bermúdez, Juan Agustín - Diccionario histórico de los mas ilustres profesores de las bellas artes en España. Edited by Miguel Morán Turina, Madrid, Akal, 2001.

[55] Muñoz y Manzano, Cipriano (called Conde de la Viñaza) - Adiciones al diccionario histórico de las más ilustres profesores de las bellas artes en España, de Juan Agustín Ceán Bermúdez, Madrid, Tipografía de los Huérfanos, 1889-1894, 4 volumes.

[56] Ossorio y Bernard, Manuel - Galería biografica de artistas españoles del siglo XIX, Madrid, Gaudi, 1975.

[57] de Lihory y Pardines, José Ruiz - Diccionario biográfico de artistas valencianos, Valencia, Imprenta de Federico Domenech, 1897.

[58] The text is however available at https://bivaldi.gva.es/es/consulta/registro.cmd?id=2367.

[59] Addison, Joseph - Los placeres de la imaginación y otros ensayos de The Spectator. Edited by Tonja Raquejo Madrid, Visor, 1991, 242 pages.

[60] Burke, Edmund - Indagación filosófica sobre el origen de nuestras ideas: de lo sublime y de lo bello, Colegio Oficial de Aparejadores y Arquitectos Técnicos de Murcia, 1985, 250 pages. A subsequent edition, edited by Menene Gras Balaguer for the Alianza editor of Madrid, was published first in 2004 and then in 2014.

[61] Gilpin, William - Tres ensayos sobre la belleza pintoresca. Introduzione di Javier Maderuel, Madrid, Abada Editores, 2004, 176 pages.

[62] Reynolds, Joshua - Quince Discursos, Ed. Poseidón, Buenos Aires, 1943, 270 pages.

[63] Reynolds, Joshua - Quince discursos pronunciados en la Real Academia de Londres, Madrid, Visor Libros, 2005.

[64] Flaxman, John – Lectures on Sculpture. As delivered before the President and Members of The Royal Academy, Henry G. Bohn, York Stree, Covent Garden, Londra, 1838, 488 pages.

[65] The text is available at the address

[44] Quatremère de Quincy, Antoine - Considérations morales sur la destination des ouvrages de l'art. (suivi de) Lettres sur l'enlèvement des ouvrages de l'art antique à Athènes et à Rome, Paris, Fayard, 1989, 256 pagine. The moral considerations published in 1832 also include the famous letters to General Miranda, published as from 1796 in a series of newspapers.

[45] Quatremère de Quincy, Antoine - Essai sur la nature, le but et les moyens de l'imitation dans les beaux-arts, Archives d'Architecture Moderne, Bruxelles, 1980.

[46] Ceán Bermúdez, Juan Agustín - Sumario de las antigüedades romanas que hay en España, en especial las pertenecientes a las Bellas Artes, Valencia, Librería París-Valencia, 2003.

[47] Encyclopédie de Diderot et d'Alembert. Edited by Andrea Calzolari e Sylvie Delassus. Parma, Franco Maria Ricci editore, 1970-1979.

[48] Quatremère de Quincy, Antoine - Diccionario de arquitectura : voces teóricas. Edited by Fernando Aliata and Claudia Shmidt, Buenos Aires, Nobuko, 2007, 245 pages.

[49] Viollet-le-Duc, Emmanuel - Dictionnaire raisonné de l'architecture française du xi au xvi siècle, Parigi, F. de Nobele, 1967, 10 volumes.

[50] Viollet-le-Duc, Emmanuel - Dictionnaire raisonné du mobilier français de l'époque carolingienne à la Renaissance, Madrid, Asociación El Cid, Madrid, 1974, 6 volumes.

[51] Martínez, Francisco - Introducción al conocimiento de las Bellas Artes. Diccionario de Pintura, Arquitectura, escultura y Grabado, Colegio Oficial de Aparejadores y Arquitectos Técnicos. Introduction by Manuel Alvar Ezquerra, Madrid, 1989, 419 pages.

[52] Rejón de Silva, Diego Antonio - Diccionario de las nobles artes para instrucción de los aficionados, y uso de los profesores, Malaga, Fundación Cultural COAM, 1989, 217 pages.

[53] De Llaguno y Amírola, Eugenio - Noticias de los Arquitectos y Arquitectura de España desde su restauracion, Madrid, Turner, 1977, 4 volumes (facsimile version of the posthumous original of 1829).

[54] Ceán Bermúdez, Juan Agustín - Diccionario histórico de los mas ilustres profesores de las bellas artes en España. Edited by Miguel Morán Turina, Madrid, Akal, 2001.

[55] Muñoz y Manzano, Cipriano (called Conde de la Viñaza) - Adiciones al diccionario histórico de las más ilustres profesores de las bellas artes en España, de Juan Agustín Ceán Bermúdez, Madrid, Tipografía de los Huérfanos, 1889-1894, 4 volumes.

[56] Ossorio y Bernard, Manuel - Galería biografica de artistas españoles del siglo XIX, Madrid, Gaudi, 1975.

[57] de Lihory y Pardines, José Ruiz - Diccionario biográfico de artistas valencianos, Valencia, Imprenta de Federico Domenech, 1897.

[58] The text is however available at https://bivaldi.gva.es/es/consulta/registro.cmd?id=2367.

[59] Addison, Joseph - Los placeres de la imaginación y otros ensayos de The Spectator. Edited by Tonja Raquejo Madrid, Visor, 1991, 242 pages.

[60] Burke, Edmund - Indagación filosófica sobre el origen de nuestras ideas: de lo sublime y de lo bello, Colegio Oficial de Aparejadores y Arquitectos Técnicos de Murcia, 1985, 250 pages. A subsequent edition, edited by Menene Gras Balaguer for the Alianza editor of Madrid, was published first in 2004 and then in 2014.

[61] Gilpin, William - Tres ensayos sobre la belleza pintoresca. Introduzione di Javier Maderuel, Madrid, Abada Editores, 2004, 176 pages.

[62] Reynolds, Joshua - Quince Discursos, Ed. Poseidón, Buenos Aires, 1943, 270 pages.

[63] Reynolds, Joshua - Quince discursos pronunciados en la Real Academia de Londres, Madrid, Visor Libros, 2005.

[64] Flaxman, John – Lectures on Sculpture. As delivered before the President and Members of The Royal Academy, Henry G. Bohn, York Stree, Covent Garden, Londra, 1838, 488 pages.

[65] The text is available at the address

https://archive.org/details/lecturesonsculpt00flaxuoft/page/n8

[66] Füssli, Johann Heinrich - Conférences sur la peinture edited by Marie-Madeleine Martinet, Parigi, École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, 2017, 270 pages.

[67] A 1848 edition is available at the address

[103] Delacroix, Eugène – Journal. 1822-1863. Edited by Lalla Romano, Milan, Abscondita, 2017, 184 pages.

[104] Delacroix, Eugène - Journal. (1822-1863), Turin, Chiantore, 1945.

[105] Corot, Camille - Corot raconté par lui-même et par ses amis, Vésenaz-Genève, P. Cailler, 1946, 2 volumes (225 e 214 pages).

[106] Constable, John - John Constable’s discourses. Edited by Ronald Brymer Beckett, Ipswich, Suffolk Records Society, 1970, 114 pages.

[107] John Constable's correspondence, edited, with introduction and notes by Ronald Brymer Beckett ; with a preface by Geoffrey Grigson, Ipswich, Suffolk Records Society, 1962-1968. Volume 1: The family at East Bergholt 1807-1837; volume 2: Early friends and Maria Bicknell (Mrs. Constable); volume 3: The correspondence with C.R.Leslie, R.A.; volume 4: Patrons, dealers and fellow artists; volume 5: Various friends, with Charles Boner and the artist's children; volume 6. The Fishers.

[108] Constable John - Further documents and correspondence. Edited by Leslie Parris; Conal Shields; Jan Fleming Williams, London, The Tate Gallery, 1975. First part: Documents, edited by Leslie Parris e Conal Shields. Second part: Correspondence, edited by Jan Fleming Williams.

[109] Carus, Carl Gustav - Cartas y anotaciones sobre la pintura de paisaje: diez cartas sobre la pintura de paisaje con doce suplementos y una carta de Goethe a modo de introducción. Edited by Javier Arnaldo. Translation by José Luis Arántegui, Madrid, Visor, 1992, 272 pages.

[110] Fragmentos para una teoría romántica del arte. Edited by Javier Arnaldo, 1987, Madrid, Tecnos, Metrópolis, 270 pagines.

[111] Friedrich, Caspar David - Kritische Edition der Schriften des Künstlers und seiner Zeitzeugen, Franfurt am Main, Kunstgeschichtliches Institut der Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität, 1999, 127 pages.

[112] Friedrich, Caspar David – Writings on art. Edited by Luisa Rubini, Milan, Abscondita, 2001, 134 pages.

[113] Anthology of sources and documents, Neoclassicism and Romanticism 1750-1850. Edited by Lorenz Eitner, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, Prentice Hall, 1970, 352 pages.

[114] Howitt, Mary Botham - Friedrich Overbeck: sein Leben und Schaffen; nach seinen Briefen und andern Documenten des handschriftlichen Nachlasses geschildert, 1886 (in two volumes).

[115] Ruskin John, Prerrafaelismo y confenrencias sobre arquitectura y pintura. Edited by Elisa Morales Veloso and Laurence Binyon, Francosco Beltrán, Madrid, Librería española y Extranyera, 1906, 333 pages.

[116] Ruskin, John - Prerrafaelismo. Conferencias sobre arquitectura y pintura. Edited by Elisa Morales Veloso, Pérez Errea e Pedro Miguel, Pamplona, Analecta, 200 pages.

[117] Boudaille, Georges – Gustave Courbet. The artist and his time, Milano, Alfieri e Lacroix, 1969, 150 pages.

[118] Courbet raconté par lui-même et par ses amis: Ses écrits, ses contemporains, sa postérité. Edited by Pierre Courthion et Jules-Antoine Castagnary. First volume: Tome 1. Sa vie et ses oeuvres. Narcisse paysan. Second volume: Comme un pommier produit des pommes.

[119] Proudhon, Pierre Joseph - Du principe de l’art e de sa destination sociale, Paris, Garnier frères, 1865, 380 pages.

[120] Proudhon, Pierre Joseph - El principio del arte : su destino social. Edited by Emilio Gutierrez de Quintanilla, Lima, Imp. de "El Nacional", 1884, 296 pages.

[121] Proudhon, Pierre Joseph - Sobre el principio del arte y sobre su destinación social. Edited by José Gil de Ramales; Arturo del Hoyo, Buenos Aires : Aguilar, 1980, 360 pages.

[122] Manet raconte par lui-même et par ses amis. Edited by Pierre Courthion. Vesenaz-Ginevra, Pierre Cailler Editeur, 1945, two volumes (251 e 500 pages).

[123] Seurat, Georges – Correspondances, témoignages, notes inédites, critiques. Edited by Eric Darragon and Hélène Seyrès, Paris, Acropole, 1991.

[124] Signac, Paul - De Eugenio Delacroix al neoimpresionismo. Edited by Julio E. Payró, Buenos Aires, Poseidón, 1943, 104 pages.

[125] Kendall, Richard - Cezanne por sí mismo : dibujos, pinturas, escritos, Esplugues de Llobregat (Barcelona) : Plaza & Janés, 1992, 320 pages.

[126] Kendall, Richard - Cézanne by himself: drawings, paintings, writings, Boston, Little, Brown, 1988, 320 pages.

[127] Cézanne, Paul – Correspondencia. Edited by John Rewald, translation by Bernardo Moreno Carrillo. Madrid, Visor, 1991, 424 pages.

[128] Cézanne, Paul - Paul Cézanne, correspondance. Edited by John Rewald, Paris : Bernard Grasset, 1937, 319 pages.

[129] Cézanne, Paul - Paul Cézanne, correspondance, recueillie, annotée et préfacée. Edited by John Rewald, Paris, B. Grasset, 1937, 319 pages.

[130] Cézanne, Paul - The letters of Paul Cézanne. Edited by Alex Danchev, Los Angeles, The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2013, 392 pagine.

[131] Correspondencia de Paul Cézanne. Edited by John Rewald, translation by Leonardo Estarico, Buenos Aires Libreria y Ed. "El Ateneo" 1948, 356 pages.

[132] Gauguin, Paul – Escritos de un salvaje, Introduction by Dolores Jiménez-Blanco. Edited by Miguel Morán Turina, Madrid, Istmo, 2000, 274 pages.

[133] Gauguin, Paul - Oviri. Écrits d'un sauvage, choisis et présentés par Daniel Guérin. Paris, Gallimard, 1974, 350 pages.

[134] Gauguin, Paul - Escritos de un salvaje. Translation by Marta Sánchez-Eguibar, Madrid, Akal, 2008, 274 pages.

[66] Füssli, Johann Heinrich - Conférences sur la peinture edited by Marie-Madeleine Martinet, Parigi, École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, 2017, 270 pages.

[67] A 1848 edition is available at the address

https://archive.org/details/lecturesonpainti02fuse/page/n6

[68] Wackenroder, Wilhelm Heinrich - Efluvios cordiales de un monje amante del arte: con una reseña de August Wilhelm Schlegel. Edited by Héctor Canal Pardo. Afterword by Cord-Friedrich Berghahn, KRK ediciones, Oviedo, 2008.

[69] Wackenroder, Wilhelm Heinrich - Works and letters. Writings of art, aesthetics and ethics in collaboration with Ludwig Tieck, German text and Italian translation by Elena Agazzi, Federica La Manna and Andrea Benedetti, Milan, Bompiani, 2014, 1276 pages.

[70] Arias Serrano, Laura - Las fuentes de la historia del arte en la época contemporánea (quoted), p.126

[71] Riegl, Alois - Problemas de estilo : fundamentos para una historia de la ornamentacion. Edited by Ignacio de Solà Morales. Barcelona, Editorial Gustavo Gili, 1980, 286 pages.

[72] Riegl, Alois - Style problems. Foundations of a history of ornamental art. Edited by Mario Pacor, Milan, Feltrinelli, 1963, 336 pages.

[73] Worringer, Wilhelm - Abstracción y naturaleza. Edited by Mariana Frenk, Mexico City, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2015, 137 pages.

[74] Worringer, Wilhelm - Abstraction and empathy. A contribution to the psychology of style. Curated by Andrea Pinotti. Translation by Elena De Angeli, Milan, Einaudi, 2008, 143 pages.

[75] Hildebrand, Adolf von - El problema de la forma en la obra de arte. Edited by Francisca Pérez Carreño, translation by María Isabel Peña Aguado Madrid, Visor, 1989, 109 pages.

[76] Hildebrand, Adolf von - The problem of form in figurative art. Edited by Andrea Pinotti and Fabrizio Scrivano, Palermo, Aesthetica, 2001, 152 pages.

[77] Fiedler, Konrad - Escritos sobre arte. Edited by Vicente Romano García, Madrid, Visor, 2005, 290 pages.

[78] Fiedler Konrad - De La Esencia Del Arte. Curated by Hans Eckstein and Manfred Schönfeld. Buenos Aires, Nueva Visión, 1958, 138 pages.

[79] Fiedler, Konrad - Writings on figurative art. Curated by Andrea Pinotti and Fabrizio Scrivano. Palermo, Aesthetica, 2006, 247 pages.

[80] Ortega y Gasset, José – La deshumanización del arte y otros ensayos de estética, Revista de Occidente, Alianza Editorial , Madrid, 1996.

[81] De Torre, Guillelmo - Literaturas Europeas De Vanguardia, Madrid, Rafael Caro Raggio, Editor, 1925, 395 pages.

[82] Gómez de la Serna Puig, Ramón – Ismos, Madrid, Biblioteca Nueva, 1931, 398 pages.

[83] De Torre, Guillelmo - Literaturas europeas de vanguardia. Edited by José Luis Calvo Carilla, Pamplona, Urgoiti, D.L. 2003, 420 pages.

[84] Gómez de la Serna Puig, Ramón – Los ismos de Ramón Gómez de la Serna y "un apéndice circense". Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, dal 5 giugno al 25 agosto 2002, 493 pages.

[85] Arias Serrano, Laura - Las fuentes de la historia del arte en la época contemporánea (quoted), p.126.

[86] Eco, Umberto - Obra abierta: forma e indeterminación en el arte contemporáneo, Barcelona: Ariel, 1990, 355 pages.

[87] Arias Serrano, Laura - Las fuentes de la historia del arte en la época contemporánea (quoted), p.163.

[88] Arias Serrano, Laura - Las fuentes de la historia del arte en la época contemporánea (quoted), p.163.

[89] Mengs, Anton Raphael, Reflexiones sobre la belleza y gusto en la pintura, Madrid: Dirección General de Bellas Artes y Archivos, 1989 ,404 pages.

[90] Mengs, Anton Raphael Mengs, Thoughts on beauty. Edited by Giuseppe Faggin, Pavia, Alessandro Minuziano publisher, 1948, 158 pages.

[91] Mengs, Anton Raphael Mengs, Thoughts on beauty. Edited by Giuseppe Faggin, Milan, Abscondita, 2003, 136 pages.

[92] Mengs, Anton Raphael Mengs, Thoughts on painting. Edited by Michele Cometa, Palermo, Aesthetica, 1996, 87 pages.

[93] Barroco en Europa. Fuentes y documentos para la historia del arte, edited by Bonaventura Bassegoda i Hugas e di José Fernández Arenas, Editorial Gustavo Gili, S.L., 477 pages.

[94] Falconet, Étienne Maurice - Writings on sculpture, edited by Cristina Conti and Diego Lorenzi, Rome, Universitalia, 2018, 152 pages.

[95] Hogarth, William - Análisis de la belleza. Edited by Miguel Cereceda, Madrid, Visor, 1997, 152 pages.

[96] Arias Serrano, Laura - Las fuentes de la historia del arte en la época contemporánea (quoted), p.163

[97] Ingres, Jean-Auguste-Dominique - Ingres raconté par lui-même et par ses amis. Pensées et écrits du peintre. Vésenaz-Genève, P. Cailler, 1947-48. In two volumes: 1. Pensées et écrits du peintre. 2. Ses contemporains sa postérité.

[98] Ingres, Jean-August-Dominique - Thoughts on art. Curated by Elena Pontiggia, Milano, Abscondita, 2019, 125 pages.

[99] Journal de Eugene Delacroix de 1822 a 1863 en 3 tomes. Edited by Andre Joubin, Ed Libraire Plon, Paris, 1932. Tome I: 1822-1852, Tome II (503 pages): 1853-1856, Tomo III (483 pages): 1857-1863 (518 pages).

[100] Delacroix, Eugène - El puente de la visión: antología de los "Diarios". Edited by María Dolores Díaz Vaillagou; Guillermo Solana Díez, Madrid, Tecnos, 2011, 151 pages.

[101] Delacroix, Eugène - Diario de Eugenio Delacroix: 1822-1863. Edited by Juan De la Encina; L Gutiérrez de Zubiaurre, Mexico City, Centauro, 1946, 316 pages.

[102] Delacroix, Eugène – Journal. Edited by Lamberto Vitali, 3 volumes, Turin, Einaudi, 1954.

[68] Wackenroder, Wilhelm Heinrich - Efluvios cordiales de un monje amante del arte: con una reseña de August Wilhelm Schlegel. Edited by Héctor Canal Pardo. Afterword by Cord-Friedrich Berghahn, KRK ediciones, Oviedo, 2008.

[69] Wackenroder, Wilhelm Heinrich - Works and letters. Writings of art, aesthetics and ethics in collaboration with Ludwig Tieck, German text and Italian translation by Elena Agazzi, Federica La Manna and Andrea Benedetti, Milan, Bompiani, 2014, 1276 pages.

[70] Arias Serrano, Laura - Las fuentes de la historia del arte en la época contemporánea (quoted), p.126

[71] Riegl, Alois - Problemas de estilo : fundamentos para una historia de la ornamentacion. Edited by Ignacio de Solà Morales. Barcelona, Editorial Gustavo Gili, 1980, 286 pages.

[72] Riegl, Alois - Style problems. Foundations of a history of ornamental art. Edited by Mario Pacor, Milan, Feltrinelli, 1963, 336 pages.

[73] Worringer, Wilhelm - Abstracción y naturaleza. Edited by Mariana Frenk, Mexico City, Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2015, 137 pages.

[74] Worringer, Wilhelm - Abstraction and empathy. A contribution to the psychology of style. Curated by Andrea Pinotti. Translation by Elena De Angeli, Milan, Einaudi, 2008, 143 pages.

[75] Hildebrand, Adolf von - El problema de la forma en la obra de arte. Edited by Francisca Pérez Carreño, translation by María Isabel Peña Aguado Madrid, Visor, 1989, 109 pages.

[76] Hildebrand, Adolf von - The problem of form in figurative art. Edited by Andrea Pinotti and Fabrizio Scrivano, Palermo, Aesthetica, 2001, 152 pages.

[77] Fiedler, Konrad - Escritos sobre arte. Edited by Vicente Romano García, Madrid, Visor, 2005, 290 pages.

[78] Fiedler Konrad - De La Esencia Del Arte. Curated by Hans Eckstein and Manfred Schönfeld. Buenos Aires, Nueva Visión, 1958, 138 pages.

[79] Fiedler, Konrad - Writings on figurative art. Curated by Andrea Pinotti and Fabrizio Scrivano. Palermo, Aesthetica, 2006, 247 pages.

[80] Ortega y Gasset, José – La deshumanización del arte y otros ensayos de estética, Revista de Occidente, Alianza Editorial , Madrid, 1996.

[81] De Torre, Guillelmo - Literaturas Europeas De Vanguardia, Madrid, Rafael Caro Raggio, Editor, 1925, 395 pages.

[82] Gómez de la Serna Puig, Ramón – Ismos, Madrid, Biblioteca Nueva, 1931, 398 pages.

[83] De Torre, Guillelmo - Literaturas europeas de vanguardia. Edited by José Luis Calvo Carilla, Pamplona, Urgoiti, D.L. 2003, 420 pages.

[84] Gómez de la Serna Puig, Ramón – Los ismos de Ramón Gómez de la Serna y "un apéndice circense". Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, dal 5 giugno al 25 agosto 2002, 493 pages.

[85] Arias Serrano, Laura - Las fuentes de la historia del arte en la época contemporánea (quoted), p.126.

[86] Eco, Umberto - Obra abierta: forma e indeterminación en el arte contemporáneo, Barcelona: Ariel, 1990, 355 pages.

[87] Arias Serrano, Laura - Las fuentes de la historia del arte en la época contemporánea (quoted), p.163.

[88] Arias Serrano, Laura - Las fuentes de la historia del arte en la época contemporánea (quoted), p.163.

[89] Mengs, Anton Raphael, Reflexiones sobre la belleza y gusto en la pintura, Madrid: Dirección General de Bellas Artes y Archivos, 1989 ,404 pages.

[90] Mengs, Anton Raphael Mengs, Thoughts on beauty. Edited by Giuseppe Faggin, Pavia, Alessandro Minuziano publisher, 1948, 158 pages.

[91] Mengs, Anton Raphael Mengs, Thoughts on beauty. Edited by Giuseppe Faggin, Milan, Abscondita, 2003, 136 pages.

[92] Mengs, Anton Raphael Mengs, Thoughts on painting. Edited by Michele Cometa, Palermo, Aesthetica, 1996, 87 pages.

[93] Barroco en Europa. Fuentes y documentos para la historia del arte, edited by Bonaventura Bassegoda i Hugas e di José Fernández Arenas, Editorial Gustavo Gili, S.L., 477 pages.

[94] Falconet, Étienne Maurice - Writings on sculpture, edited by Cristina Conti and Diego Lorenzi, Rome, Universitalia, 2018, 152 pages.

[95] Hogarth, William - Análisis de la belleza. Edited by Miguel Cereceda, Madrid, Visor, 1997, 152 pages.

[96] Arias Serrano, Laura - Las fuentes de la historia del arte en la época contemporánea (quoted), p.163

[97] Ingres, Jean-Auguste-Dominique - Ingres raconté par lui-même et par ses amis. Pensées et écrits du peintre. Vésenaz-Genève, P. Cailler, 1947-48. In two volumes: 1. Pensées et écrits du peintre. 2. Ses contemporains sa postérité.

[98] Ingres, Jean-August-Dominique - Thoughts on art. Curated by Elena Pontiggia, Milano, Abscondita, 2019, 125 pages.

[99] Journal de Eugene Delacroix de 1822 a 1863 en 3 tomes. Edited by Andre Joubin, Ed Libraire Plon, Paris, 1932. Tome I: 1822-1852, Tome II (503 pages): 1853-1856, Tomo III (483 pages): 1857-1863 (518 pages).

[100] Delacroix, Eugène - El puente de la visión: antología de los "Diarios". Edited by María Dolores Díaz Vaillagou; Guillermo Solana Díez, Madrid, Tecnos, 2011, 151 pages.

[101] Delacroix, Eugène - Diario de Eugenio Delacroix: 1822-1863. Edited by Juan De la Encina; L Gutiérrez de Zubiaurre, Mexico City, Centauro, 1946, 316 pages.

[102] Delacroix, Eugène – Journal. Edited by Lamberto Vitali, 3 volumes, Turin, Einaudi, 1954.

[103] Delacroix, Eugène – Journal. 1822-1863. Edited by Lalla Romano, Milan, Abscondita, 2017, 184 pages.

[104] Delacroix, Eugène - Journal. (1822-1863), Turin, Chiantore, 1945.

[105] Corot, Camille - Corot raconté par lui-même et par ses amis, Vésenaz-Genève, P. Cailler, 1946, 2 volumes (225 e 214 pages).

[106] Constable, John - John Constable’s discourses. Edited by Ronald Brymer Beckett, Ipswich, Suffolk Records Society, 1970, 114 pages.

[107] John Constable's correspondence, edited, with introduction and notes by Ronald Brymer Beckett ; with a preface by Geoffrey Grigson, Ipswich, Suffolk Records Society, 1962-1968. Volume 1: The family at East Bergholt 1807-1837; volume 2: Early friends and Maria Bicknell (Mrs. Constable); volume 3: The correspondence with C.R.Leslie, R.A.; volume 4: Patrons, dealers and fellow artists; volume 5: Various friends, with Charles Boner and the artist's children; volume 6. The Fishers.

[108] Constable John - Further documents and correspondence. Edited by Leslie Parris; Conal Shields; Jan Fleming Williams, London, The Tate Gallery, 1975. First part: Documents, edited by Leslie Parris e Conal Shields. Second part: Correspondence, edited by Jan Fleming Williams.

[109] Carus, Carl Gustav - Cartas y anotaciones sobre la pintura de paisaje: diez cartas sobre la pintura de paisaje con doce suplementos y una carta de Goethe a modo de introducción. Edited by Javier Arnaldo. Translation by José Luis Arántegui, Madrid, Visor, 1992, 272 pages.

[110] Fragmentos para una teoría romántica del arte. Edited by Javier Arnaldo, 1987, Madrid, Tecnos, Metrópolis, 270 pagines.

[111] Friedrich, Caspar David - Kritische Edition der Schriften des Künstlers und seiner Zeitzeugen, Franfurt am Main, Kunstgeschichtliches Institut der Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität, 1999, 127 pages.

[112] Friedrich, Caspar David – Writings on art. Edited by Luisa Rubini, Milan, Abscondita, 2001, 134 pages.

[113] Anthology of sources and documents, Neoclassicism and Romanticism 1750-1850. Edited by Lorenz Eitner, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, Prentice Hall, 1970, 352 pages.

[114] Howitt, Mary Botham - Friedrich Overbeck: sein Leben und Schaffen; nach seinen Briefen und andern Documenten des handschriftlichen Nachlasses geschildert, 1886 (in two volumes).

[115] Ruskin John, Prerrafaelismo y confenrencias sobre arquitectura y pintura. Edited by Elisa Morales Veloso and Laurence Binyon, Francosco Beltrán, Madrid, Librería española y Extranyera, 1906, 333 pages.

[116] Ruskin, John - Prerrafaelismo. Conferencias sobre arquitectura y pintura. Edited by Elisa Morales Veloso, Pérez Errea e Pedro Miguel, Pamplona, Analecta, 200 pages.

[117] Boudaille, Georges – Gustave Courbet. The artist and his time, Milano, Alfieri e Lacroix, 1969, 150 pages.

[118] Courbet raconté par lui-même et par ses amis: Ses écrits, ses contemporains, sa postérité. Edited by Pierre Courthion et Jules-Antoine Castagnary. First volume: Tome 1. Sa vie et ses oeuvres. Narcisse paysan. Second volume: Comme un pommier produit des pommes.

[119] Proudhon, Pierre Joseph - Du principe de l’art e de sa destination sociale, Paris, Garnier frères, 1865, 380 pages.

[120] Proudhon, Pierre Joseph - El principio del arte : su destino social. Edited by Emilio Gutierrez de Quintanilla, Lima, Imp. de "El Nacional", 1884, 296 pages.

[121] Proudhon, Pierre Joseph - Sobre el principio del arte y sobre su destinación social. Edited by José Gil de Ramales; Arturo del Hoyo, Buenos Aires : Aguilar, 1980, 360 pages.

[122] Manet raconte par lui-même et par ses amis. Edited by Pierre Courthion. Vesenaz-Ginevra, Pierre Cailler Editeur, 1945, two volumes (251 e 500 pages).

[123] Seurat, Georges – Correspondances, témoignages, notes inédites, critiques. Edited by Eric Darragon and Hélène Seyrès, Paris, Acropole, 1991.

[124] Signac, Paul - De Eugenio Delacroix al neoimpresionismo. Edited by Julio E. Payró, Buenos Aires, Poseidón, 1943, 104 pages.

[125] Kendall, Richard - Cezanne por sí mismo : dibujos, pinturas, escritos, Esplugues de Llobregat (Barcelona) : Plaza & Janés, 1992, 320 pages.

[126] Kendall, Richard - Cézanne by himself: drawings, paintings, writings, Boston, Little, Brown, 1988, 320 pages.

[127] Cézanne, Paul – Correspondencia. Edited by John Rewald, translation by Bernardo Moreno Carrillo. Madrid, Visor, 1991, 424 pages.

[128] Cézanne, Paul - Paul Cézanne, correspondance. Edited by John Rewald, Paris : Bernard Grasset, 1937, 319 pages.

[129] Cézanne, Paul - Paul Cézanne, correspondance, recueillie, annotée et préfacée. Edited by John Rewald, Paris, B. Grasset, 1937, 319 pages.

[130] Cézanne, Paul - The letters of Paul Cézanne. Edited by Alex Danchev, Los Angeles, The J. Paul Getty Museum, 2013, 392 pagine.

[131] Correspondencia de Paul Cézanne. Edited by John Rewald, translation by Leonardo Estarico, Buenos Aires Libreria y Ed. "El Ateneo" 1948, 356 pages.

[132] Gauguin, Paul – Escritos de un salvaje, Introduction by Dolores Jiménez-Blanco. Edited by Miguel Morán Turina, Madrid, Istmo, 2000, 274 pages.

[133] Gauguin, Paul - Oviri. Écrits d'un sauvage, choisis et présentés par Daniel Guérin. Paris, Gallimard, 1974, 350 pages.

[134] Gauguin, Paul - Escritos de un salvaje. Translation by Marta Sánchez-Eguibar, Madrid, Akal, 2008, 274 pages.

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento