Keith Haring

Journals

Introduction by Robert Farris Thompson

Foreword by David Hockney

Penguin Books Classics, 2010, 464 pages

Review by Francesco Mazzaferro. Part Four

Go Back to Part One

Keith Haring and political

commitment

The

image we are drawing from Keith Haring's Journals

would not be complete if we did not refer to their more political pages. The

caveat we have already repeated several times during this review is always

valid: Keith was certainly not a Gandhi nor a Martin Luther King; his testimony

and adherence to civil battles always remained on an individual basis and his

messages were translated into iconographic, not dialogical forms of protest. It

should also be remembered that the years in which Haring lived were often

qualified as 'the age of political disengagement'. The artist was however

living in New York’s East Village, where political commitment was a norm; he

recalled, for example, to have participated very young at the "Nova Convention", an event during

which many American artists gathered in the US metropole in 1979 to give

strength to a series of civil battles, so much so that, according to what he

wrote, "Nova Convention changed my

life” [123]. However,

the society, more generally, began to show tiredness for public engagement and

tent to take refuge in the private sector. In any case, Haring was certainly a

committed artist, but I do not think we can talk about him as a fully political

artist.

One

of the most ambiguous aspects of his person was his relationship with wealth.

On the one hand, in the second part of the Journals

it becomes evident how the young painter (only shortly before a student without

much economic means) had no difficulty to bear the weight of success, attending and living in

circles marked by the exhibition of luxury. On the other, in the pages of the Journals of those same years, he made

frequent critical comments to the application of the model of capitalist

society to the world of art. (“The whole

concept of “business” is evil. (…) Business is only another name for control.

Control of mind, body and spirit. Control is evil [124]).

The

way Keith tried to reconcile the two opposites was to agree to be part of a

world dominated by commercial consumption, while trying to avoid the most

excessive aspects of it. For example, on the track of the Pop Art artists,

Haring also tried to create market channels that allowed him to sell his works

of art at a price accessible to everyone. He himself realized how the result

could be ambiguous: even his most political art would be liable, in fact, to be

commodified: “It’s really satisfying to

make the things and really fulfilling to see people’s response to them, but the

rest is difficult. I tried, as much as I could, to take a new position, a

different attitude about selling things, by doing things in public and by doing

commercial things that go against the ideas of the “commodity-hype” art market.

However, even these things are co-opted and seen by some as mere advertising

for my salable artworks. I fear there is no way out of this trap. Once you

begin to sell things (anything) you are guilty of participating in the game.

However, if you refuse to sell anything you are a non-entity” [125]. The problem was objective (a philosopher

would write it was ontological) and went well beyond the intentions of the

artist, because it depended on the attribution of an economic value to any

object, in the very moment in which it was produced: “It is impossible to separate the activity and the result. The act of

creation itself is very clear and pure. But this creation immediately results

in a “thing” that has a “value” that must be reckoned with. Even the subway

drawings, which were quite obviously about the “act,” not the “thing,” are now

turning up, having been “rescued” from destruction by would-be collectors.

Possibly only the murals on cement walls that cannot be removed and the

computer drawings, which can be rearranged at will, are free from these

considerations” [126].

One

of the aspects that the artist proved to know through direct experience was

that of the speculative manipulation of the art market. Haring was well aware

of the mechanisms by which critics identified unknown young artists, created

the embryonic attention of the market and stimulated the interest of gallery

owners. In this way young artists realized that they could start making small

profits, buy new materials, increase production, meet the public demand and

begin to become known, even if not yet famous. It was a process that Keith

described in detail [127], not failing to emphasize that it was also leading to

the separation between artist and their initial circles of friends, as they now

would no longer consider him one of them, but a part - even if still very

marginal - of that market that they generally despised. “The more work you sell, the more demand there is by word-of-mouth by

the people who are “collecting” it. Many people begin to think of you as a

risky investment, but an investment nonetheless. Since the work is still

inexpensive they can afford this small risk” [128]. Quotations would raise, articles of critics and quotations in the

media would multiplying, and a new speculative bubble would be born: the

paintings would be sold at auctions, because the first investors (those

specialized in bringing out new artists, only some of whom would impose themselves

in the market) would try to realize the gains before they would fade, and

others instead would rush to buy at still low prices, thinking about future

earnings. However, to ensure such gains on past works, it would be key that the

rising stard in the art would would not exceed with the creation of new works; their main

concern would become that of ensuring the desired optimal balance between past

and future production. At that point the artist himself would risk becoming a

speculating agent. It is really interesting how the pages of Haring coincided

perfectly with those that the American art historian Grete Ring (1887-1952) wrote in 1931 to describe the functioning of the art market in Paris (also

dominated by the speculative game between traders who specialized in launching

new talents, on the left bank of the Seine, and traders who wanted to make

money from their success on the established market, on the right bank of the

Seine). Sixty

years later, things were functioning in New York at the same time as in Paris

before.

Fig. 16) The announcement of the exhibition on Keith Haring held in Bologna’s National Art Gallery in 2018

|

Returning

to the painter's civil activism, it is known that Haring became one of the

icons of the struggle for freedom and the integration of homosexual

communities, also thanks to his commitment against the spread of the AIDS

epidemic, which saw him realize many images in favour of safe and secure sex.

There are famous photos that portray him in Kansas City along with a series of

intellectuals, in September 1987, in a protest against the spread of AIDS, with

a shirt bearing the inscription “AIDS is

Political-Biological Germ Warfare” [129]. In fact, Haring adhered to the

'conspiracy' theses on the spread of the disease: in those years the rumour was

born that the virus would not be the result of the mutation of a disease

originally widespread among the primates in Africa, but the result of a process

laboratory, run away the hands of scientists, and originally brought forward to

prepare the war through the creation of viruses and bacteria intended to

inflict severe predictions to enemies. A further account that was supported by

the conspiracy theorists wanted that AIDS, once generated in test tubes, had

been deliberately disseminated in the United States, starting from California,

to exterminate the gay community, which had just claimed its rights in the

previous decade.

The fight against the disease and the battle for the claim of

a free sexuality were interwoven, in the case of Haring, with the broader

phenomenon of the oppression of all minorities. Here is what Keith wrote when

he learnt that all those accused for the killing of graffiti artist Michael Stewart (1958-1983), a black street artist who died in police custody after

being arrested while trying to paint on the street, had been acquitted. These were

words full of anger and frustration: “Most

white men are evil. The white man has always used religion as the tool to

fulfil his greed and power-hungry aggression. (…) All stories of white men’s

“expansion” and “colonization” and “domination” are filled with horrific

details of the abuse of power and the misuse of people. I’m sure inside I’m not

white. There is no way to stop them, however. I’m sure it is our destiny to

fail. The end is inevitable. So who cares if these pigs kill me with their evil

disease, they’ve killed before and will continue to kill until they suck

themselves into their own evil grave and rot and stink and explode themselves

into oblivion. I’m glad I’m different. I’m proud to be gay. I’m proud to have

friends and lovers of every color. I am ashamed of my forefathers. I am not like them” [130].

|

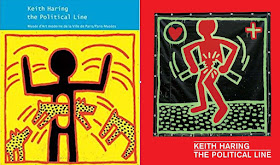

| Fig. 17) The invitation to the vernissage of the "Made in New York" exhibition on Keith Haring, held in Florence on October 25, 2017. |

Keith

was therefore convinced of living in a commodified and fundamentally bad world;

in such a gloomy picture, one of the few aspects that comforted him was the

fact of being able to realize many works in public places, in such a way as to

make them immediately accessible to good people (first of all children). It was

this idea of direct and immediate contact with the public that perhaps made his

art more political than the contents of the same (with some exceptions) were: “Most

of these paintings are put in public places (i.e., schools, hospitals, swimming

pools, parks, etc.) and quite rarely do any of them receive a negative

reaction. In fact, I have found the public quite anxious to accept and

appreciate my work, while the bourgeois and the “critical art world” is much

less receptive and feel themselves to be “above” such work” [131].

What being an artist means

We

have already seen, in the first part of the Journals,

that Keith wondered about the meaning of his activity as artist. In the summer

of 1987, in the weeks spent peacefully in Knokke, perhaps forgetting the

disease and the harbinger of death, Haring raised again the same questions,

trying to define the strengths and weaknesses of his profession. Artists change

the world, as they are not pure aesthete; it is precisely thanks to the

production of beauty that they have a superior ability to understand things and

get in touch with reality. These were very beautiful pages, inspired by a sense

of rare satisfaction in those years, and which were worth reading as a testimony

of an artist who assigned to his work a superior sense than the simple

production of consumer goods. Furthermore, those pages also stated the view that the

artist's work must be conscious, reflected and mindful. In these pages, Keith

was in continuity with an entire tradition of artistic literature that, from the

second half of the sixteenth century onwards, affirmed the nobility of art. “Somewhere, herein, lies the importance of

being an artist. Artists help the world go forward, and at the same time make

the transition smoother and more comprehensible. Often it is difficult to

isolate the actual effect of artists on the physical world of “reality”: their

effect is so much a part that it is part of the interpretation or experience of

“reality” itself. We see as we have been taught “to see” and we experience as

we have “been shown” to experience. Each new creation becomes part of the

interpretation/definition of the “thing” that will come next; at the same time

becoming a kind of summation of everything that has preceded it. This constant

state of flux is recorded in time by events and within events by the “things”

that populate, define and compose these events. Since he creates them, these

“things” are the responsibility of the artist. They must be constructed with

care and consideration (aesthetics) since it is these “things” alone that will

bring “meaning” and “value” to events and consequently our lives. By artists, I

don’t mean only painters and sculptors and musicians, writers, dramatists, dancers,

etc., etc., but all forms of artists

within the labor force: carpenters, plumbers, draftsmen, cooks, florists,

bricklayers, etc., etc. Every decision is, after all, an aesthetic decision

when you are changing, arranging, creating, destroying, or imagining “things”.”[132]. Thus, the definition of art, in its noblesse,

was so broad to also include carpenters.

The

universality of art (understood here in the sense that every human activity has

the ability to create new realities, and therefore to initiate a cycle of

innovation in the physical world), can be fully understood, according to Keith,

only if one takes distance and freeze himself from the constraints of modern

life. Here he resumed indirectly the myths of the good savage, as well as those

that assign to art a religious sense. After all, this page revealed the

cultural dependence of Haring (and probably of the entire East Village circles)

from nineteenth-century romanticism. “So-called

“primitive” cultures understood the importance of this concept being applied to

every aspect of their lives. This helped to create a very rich, meaningful

existence in total harmony with the physical “reality” of the world.

Contemporary man, with his blind faith in science and progress, hopelessly

confused by the politics of money and greed and abuse of power, deluded by what

appears to be his “control” of “the situation,” etc., etc., believes in his

“superiority” over his environment and other animals. He has lost touch with

his own sense of purpose or meaning. Most religions are so hypocritically

outdated, and suited to fit the particular problems of earlier times, that they

have no power to provide liberation and freedom, and no power to give “meaning”

beyond an empty metaphor or moral code. (…) The only way that this cycle

becomes enriched, and hence more fruitful and meaningful, is through the

insertion of aesthetic manipulation” [133].

Favourite and hated artists

What

judgments did Haring express on the artists of his time in the second part of

the Journals (1986-1989)? We have already

spoken of his personal preference for colleagues like Jean Dubuffet

(1901-1985), Pierre Alechinsky (1927-) and Brion Gysin (1916-1986). His sense

of admiration and gratitude for Andy Warhol (1928-1987) is obvious, as he

considered him a spiritual father and the author of an art of “timeless and monumental quality” [134];

equally manifest was his friendship with Kenny Scharf (1958-) and Jean-Michel

Basquiat (1960-1988), whom he frequented in the East Village. Let us now try to

draw Haring's opinions on other artists of his time.

Niki de Saint-Phalle and Jean

Tinguely

Keith's

relationship with Niki de Saint Phalle (1930-2002) and Jean Tinguely

(1925-1991), well-established artists since the 1960s, was one of the most

intense among those documented in the Journals.

Once a couple in the 1960s and married since 1971, Niki and Jean lived separate

lives over the years documented in these pages, but had remained friends: they cooperated

as artists and had a circle of common friends. Keith was in fact one of them, even

if, most of the time, he met them separately.

Keith

and the couple of artists had known each other since 1983. About them, Haring

spoke in the Journals, for the first

time, only on March 28, 1987. He went to Munich to attend the exhibition

dedicated to Niki at the Kunsthalle. “I

went there for Niki de Saint-Phalle’s show, but mostly to meet Jean Tinguely at

his opening. The funniest thing was the big fat German ladies standing in front

of Niki’s sculptures looking exactly like the big fat sculptures! Jean was fun

as usual! Very fast and very fun. He brought masks to the boring lunch and

turned the atmosphere around immediately!” [135]. There were many opportunities for

meetings: on June 15 of the same year Keith met Jean in Geneva, together with

Pierre Keller (1945-), a Swiss artist and critic [136]. Also in 1987 Keith

visited Niki in Paris, where the sculptor guided him not only in his own house,

with a rich collection of both his and Jean's works, but also in a wood near

his home where some of Jean's works were located. Here is the description of

the Cyclops, the huge head-shaped

statue with one eye made by Tinguely since 1969 and to which he continued to work

until his death. For Keith it was an experience that combined play and dream: “Niki takes us to the forest near her house

to see the “head” Jean and others have been working on for 15 years. It’s

really incredible - huge and actually has movable parts. It’s better than

Disneyland. You can walk inside of it and climb stairs all through it. It has a

theatre and an apartment inside. I’ve seen pictures of it and have wanted to

see it (…). She also takes us to see Hean’s house where she used to live also.

It is a really old (medieval) castle with sheep running around outside”

[137].

The

strongest link, though, was with Jean. With him Keith discussed everything, so

much so that the list of topics on which they conversed on a joined car trip from Brussels

airport to Knokke, in October 1987, occupied a full page. For Haring, Tinguely was

a person with whom he had managed to establish a deep human and artistic

understanding: “He’s so cool, he

understands how I understand calligraphy, and he gives me a lot of credit for

things others don’t notice. He really makes me feel at home. We did some cool

drawings together, mostly me adding to drawings he had done earlier, but we

decided next time to start from scratch and be more equal in our efforts. Our

drawing habits complement each other nicely” [138].

|

| Fig. 18) The poster of the retrospective on Jean Tinguely held in Paris at the Centre Pompidou between 8 December 1988 and 27 March 1989 |

In

February 1989 Keith went to Paris to see the Tinguely retrospective at the Centre

Pompidou. What he admired the most was Tinguely's ability to hit the visitor,

inspiring in him the most varied feelings. From Keith's admired reactions to

the art of Jean it is confirmed that, for Haring, an essential aspect of the

artist's production was his ability to talk with the public (especially with

children). “Jean Tinguely’s show is (…)

really incredible (…). A lot of new pieces made in 1988. It’s great to see this

work since he was close to death a year and a half ago. (…) Also great to see

people’s reaction /participation to/with these pieces. Children are compelled

to touch them and gaze in wonderment. It’s totally enchanting and accessible on

many levels. (…) It is a totally aggressive exhibition. The viewer is forced

into submission. This is a rare instance.

Most exhibitions only achieve this with an active permission granted by the

viewer. You can “let” yourself be seduced. This work forces you (however politely)

to see it, feel it, become it. Children’s reactions to it make its impact quite

clear. I was watching faces of people looking as much as I watched the works.

It’s a wonderful lesson. In some ways I always strive for this, but only

occasionally achieve it. It is the ultimate reaffirmation” [139].

|

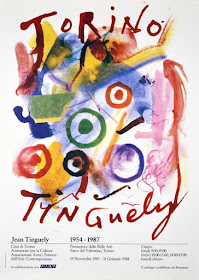

| Fig. 19) The poster of Jean Tinguely's exhibition in Turin, between November 1987 and January 1988 |

Keith's

attention then focused on a single piece: “There

was a piece from 1967 called “Requiem for a Dead Leaf” that is a huge machine

(a series of pulleys, wheels, belts) that is entirely black, intricately

constructed, and serves the sole purpose of causing movement of a white piece

of metal with a dead leaf (maybe cast) attached to it. The whole complicated

mechanism exists for this one small movement. This piece really freaked me out

because it is the closest manifestation I have ever seen to the “dream” I have

had continually since I was a small child, often accompanied by a high fever or

appearing in times of despair. I haven’t had it for a while now, but remember

the feeling of isolation that accompanied it and of often going into this state

of “leaving my body” during some intense moments. (…) This sculpture is the

first time I’ve seen anything that immediately brought me back to this dream.

Incredible” [140]. Haring visited the exhibition again on March 16th,

coming out even more satisfied [141]. Keith and Jean still met on June 29th (“Jean Tinguely came. It was great as usual”

[142].) and on September 1, 1989 (“I saw

Jean Tinguely in his new studio, and finally chose a great sculpture for our

trade. It is really a good one and just in time for my new apartment.”)

[143]. It was one of the last pages of the diary, which was interrupted on

September 22 (five months before death).

George Condo

One

of Keith's great friends was George Condo (1957-), a painter from the East

Village of New York, very close to Basquiat. In fact, Haring and Condo only knew

each other personally in Europe. The Journals

often cited him, even if it was often the simple recording of fleeting

encounters. At least in the pages I am reviewing here, the two meet for the

first time in Munich in March 1988, on the occasion of an exhibition held at

the local Kunstverein [144]. Shortly afterwards, Haring read an interview

of the painter published in the catalogue and remained conquered by the

artist's depth; in particular, he was struck by his statement that art is more

important than life, because it is immortal [145]. That sentence struck him,

probably for the shortness of his life expectancy. Keith and George met again a

month later in Paris, and since then Condo became one of the stable presences

of all his French nights [146]. It was

Condo who introduced him to Picasso's son, Claude (1947-), who would become

another of the painter's closest friends. The meeting opportunities then became

so frequent that it was not worth enumerating them. Keith's attitude was

benevolent, even when he happened to report a terrible fight between Condo and

his wife in a London hotel that led to the destruction of a precious mirror of

the hotel room, to the wounding of the woman and to the flooding of the

bathroom in the room [147].

The

next day Haring went to see a Condo exhibition and wondered how it was possible

that a man who had just destroyed a room and injured his wife could produce

such beauty. But the judgment on the friend did not change: “Woke up late. Went to see Condo’s show at

Waddington. It’s really amazing. I truly enjoy seeing things that knock me off

my feet like this. It is totally inspirational and makes you want to go home

and work immediately. (…) The viewer finds himself constructing a “pretty” picture in his head

from a chaos of seemingly unrelated shapes and colors. (…) Some drawings are

downright ridiculous, but somehow they become transformed by all of our

“knowledge” and preconceived ideas and remembrances of “art” and we invent a new thing

in our own heads that combines our expectations with what is before us. He

walks a very thin, but very important, line. (…) The large painting at the

entrance (which is also the cover of the catalogue) is remarkable. It combines

dozens of already great drawings into a collage of drawing and painting that

truly exceeds the sum of its parts. The thing that always intrigues me about

George’s things is how they grow on you and keep changing. When you see them

months later, you remember things you saw the first time and seek them out, but

also you are overwhelmed by new things you hadn’t noticed the first time. They

really have a life of their own” [148].

Francesco Clemente

One

of the artists about whom Keith spoke with great warmth and admiration in the Journals was Francesco Clemente (1952-).

Haring visited Bruno Bischofberger's gallery in Zurich in October 1987 to

admire his paintings on display (Bischofberger was one of Clemente's greatest

gallery owners) [149]. Keith remembered his family fondly in New York [150]. He

also admired the book "India", which he saw in Tokyo [151]. He

finally visited the studio in Naples [152]. The Journals did not contain however any evaluation of the works.

Frank Stella

Haring

considered it so important to make his judgment (though negative) on the art of

Frank Stella known, that the pages dedicated to him in the Journals [153] were among the very few that referred to New York.

In fact, he wrote these words as soon as he had left the NY exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, entitled

"Frank Stella: Works from 1970 to 1987."

|

| Fig. 20) The catalog of the retrospective on Frank Stella, held at the MoMA in New York from October 12, 1987 to January 5, 1988 |

Haring's

assessment was very precise: he considered Stella's art cold and too rational. “I just left the Frank Stella retrospective

(his second) at MoMA. A few observations: The big square geometrical paintings

(about 12 feet square) look more “pop” than anything else. They look like

stereotype “modern” paintings. Pure modern, abstract painting, but more than

that they seem to be a summation of this kind of flat, color-field, abstract,

geometrical painting. Almost a joke about this kind of painting” [154].

At

the same time, it seemed to him that Stella had created an excessive art, in

terms of size, and too violent, in the choice of colors. “The viewer is overwhelmed and consumed by the scale alone. Colors

geometrically, mathematically chosen. (…) The schlocky paint job and horrible

color combinations seem to be an attempt to surpass the Abstract Expressionists

again. Proving he can do it. Proving it doesn’t matter how meaningless the

marks look and how haphazard the choice of colors is” [155]. In

fact, what most stroke Keith's sensitivity was the fact that an art critic,

such as Robert Hughes (1938-2012), assigned Stella a fundamental role in the

artistic affirmation of street art, thus occupying a terrain that, in his

opinion, belonged instead to him: “But it

is infuriating for assholes like Robert Hughes to say things about how Stella

was the only artist capable of translating the “graffiti-like” use of garish

colors and gestures into a successful art work” [156]. And it is evident that there was an element of envy: “Yes, this is Frank Stella’s second

retrospective at MOMA. They have not even shown one of my pieces yet. In their

eyes I don’t exist” [157].

Julian Schnabel

Julian

Schnabel (1951-) certainly did not belong to the artists of his generation

who conquered Keith’s heart. He was then known to the general public especially

as a young assault painter, while today he is above all an established film

director. Schnabel was famous in those years for the combination of painting

and the use of materials (such as, for example, “broken plates, straw, wax, and wooden constructions” [158]) applied

on it. Keith’s judgment was merciless: “Art

is, after all, about the image we have before us, the lasting impact and effect

that image has on us, not only the ego of the artist whose obsession with

himself prevents him from seeing the larger picture. Julian Schnabel is not a

genius. He’s probably not even a great painter. I’m sure that he is interesting

today in a limited capacity and he is very interesting for collectors and

dealers, but in the long run, his contribution is slight. Joseph Beuys has

already explored most of the territory of the ambiguous figurative abstraction

that Julian Schnabel pretends to have invented” [159]. It should be noted that on April 25, 1987, Haring met Schnabel in

Düsseldorf, on the occasion of an exhibition in which he exhibited works from

1975 to 1986. The judgment, in this case, was much more positive, even if very

brief: “Call Julian Schnabel at hotel

(he’s in same hotel) and arrange to see him at his show. He’s installing a show

at the museum. It looked good” [160].

Illness and death

Keith

was very discreet about his disease. Certainly, since he understood in March

1987 that he had been infected, the tone of his pages became bleaker. In those

years the simple diagnosis equalled to an automatic and instantaneous synonym

of death. However, the painter did not seem to panic: “I’m not really scared of AIDS. Not for myself. I’m scared of having to

watch more people die in front of me. Watching Martin Burgoyne or Bobby die was

pure agony. I refuse to die like that. If the time comes, I think suicide is

much more dignified and much easier on friends and loved ones. Nobody deserves

to watch this kind of slow death. I

always knew, since I was young, that I would die young. But I thought it would

be fast (an accident, not a disease).

In fact, a man-made disease like AIDS. Time will tell, but I am not scared. I

live every day as if it were the last. I love life” [161]. Of course, he was

very disturbed by the fact that periodically unauthorised rumours spread in New

York about his state of health, so as that he was receiving worried phone calls

by friends and acquaintances during his European travels [162]. As time passed, the regret for lost

health became stronger. On April 30, 1987, he was in despair of not being able

to reach fifty years: “I would love to

live to be 50 years old. Imagine ... hardly seems possible. Not for me ...”

[163]. In October of the same year he

dreamed of having children and that thought led him to reflect on death and

what would remain after it: “Sometimes I

really wish I could have my own children, but maybe this is a much more

important role to play in many more lives than just one. Somehow I think this

is the reason I’m still alive. Speaking of being alive, I really miss Andy

sometimes. People are always bringing up the subject of his absence. I wonder

if people will miss me like that? What a selfish thought! Do artists only make

art to assure their immortality? In search of immortality: maybe that’s it ... ” [164]. On September 21, 1989

he spoke of “the new information I

received last week about my wealth” and commented: “I owe it to myself to think for myself for a change” [165]. On

the day after the Journals ended.

Keith Haring passed away on February 16, 1990.

NOTES

[124] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), p.164.

[125] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), p.210.

[126] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), pp.210-211.

[127] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), pp.249-250.

[128] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), p.250.

[129] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), p.227.

[130] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), pp.165-166.

[131] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), pp.244-245.

[132] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), p.213.

[133] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), p.214.

[134] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), p.159.

[135] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), p.161.

[136] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), p.202.

[137] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), p.223.

[138] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), p.241.

[139] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), pp.310-311.

[140] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), pp.311-312.

[141] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), p.341.

[142] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), p.355.

[143] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), p.361.

[144] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), p.161.

[145] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), p.162.

[146] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), p.166.

[147] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), p.330.

[148] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), pp.331-332.

[149] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), p.238.

[150] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), p.239.

[151] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), p.256.

[152] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), p.363.

[153] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), pp.273-277.

[154] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), p.273.

[155] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), pp.273-274.

[156] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), p.275.

[157] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), p.276.

[158] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), p.160.

[159] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), p.160.

[160] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), p.168.

[161] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), p.163.

[162] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), p.175 e pp.194-195.

[163] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), p.173.

[164] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), p.239.

[165] Haring, Keith – Journals, (quoted), pp.365-366.

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento