Review by Giovanni Mazzaferro

Translation by Francesco Mazzaferro

CLICK HERE FOR ITALIAN VERSION

Sylvie Neven

The Strasbourg Manuscript

A Medieval Tradition of Artists’ Recipe Collections (1400-1570)

Londra, Archetype Publications, 2016

Sylvie Neven

The Strasbourg Manuscript

A Medieval Tradition of Artists’ Recipe Collections (1400-1570)

Londra, Archetype Publications, 2016

To define

this book merely as the latest English critical edition (and the second

integral one) of the Strasbourg Manuscript would be quite restrictive. The

volume of Ms Sylvie Neven starts from the manuscript study (or, better said, of

its copy) to reconstruct a set of other manuscripts (a "Tradition"; in fact, from now on

the term will be used in this meaning with the capital "t") which

shares with it part of their contents; in turn, the works that are part of the

Tradition are contextualized within a genre which in German took the name of Fachliteratur (i.e. "specialist

literature"). The Fachliteratur,

covering medicine, alchemy, artistic techniques etc. is, fundamentally, a

literature based on recipes, with its own syntax and features. The authoress

studies the possible origins of this type of literature, the similarity between

recipes of different nature, the areas of their origination, the possible

authors and the drafters of the manuscripts; in workshops and in the few

artefacts of that era which survived to the present day, she also searches

comparisons with the findings of the techniques described in the texts. Sylvie

Neven’s book is therefore, more than a critical edition, a fascinating journey

into the world of medieval recipes.

The Strasbourg Manuscript

The Strasbourg Manuscript does not exist

anymore. The specimen presenting him was preserved with the mark A VI 19 at the

library of the Alsatian town, probably coming from the cards of the local St

John's Commandery, founded in the fourteenth century (see p. 14). It was

destroyed during the disastrous fire that hit the town in 1870 (purely

incidentally, it should be remembered that it was not an unfortunate event, but

one of the results of the Franco-Prussian War, the first episode of a series of

conflicts for the control of Alsace and Lorraine, which only ended with World War

II after the death of several millions of German and French citizens).

Fortunately, in previous years, the manuscript had been studied by Charles Lock Eastlake, great expert and director of the National Gallery, and the author of

the Materials for a History of Oil

Painting in 1847. Eastlake published some excerpts in his collection

dedicated to the history of oil painting. To better examine it, he commissioned

a copy, which is kept at the National Gallery, in London, with mark 75,023 STR.

We do not know anything of that copy, as we ignore who produced it, whether it

was complete, and whether it complied with certain criteria required by Eastlake.

Actually, Sylvie Neven states today, with reasonable probability, that it was a

corrupt text, where some topics had been left out or otherwise moved from their

original location. The first complete edition of the Strasbourg Manuscript was made by Ernst Berger, which made another

copy from that of Eastlake and published it within the three volumes that displayed

his 1897 Quellen und Technik der Fresko-,

Öl- , und Tempera-Malerei. The first English complete edition, edited by the

sisters Violet and Rosamund Borradaile, dates back to 1966. There were no other

translations.

The

historical importance of the work was well understood since the time of

Eastlake, who pointed out that, among the various recipes, there were some who

also covered the production and the use of a drying oil for panel painting.

The general structure of the manuscript was set by Berger with a subdivision

into three parts, all independent of each other; the first consisted of a short

series of recipes that the scribe said to have been transmitted by Henry of

Lubeck; the second one of requirements dictated by Andrew of Colmar; in the third

one the writer (we do not know who he was) spoke in the first person, and seemed

to refer to his personal experience. The lost exemplary, according to palaeographic

studies commissioned by Eastlake, dated back to the fifteenth century and was

written in an ancient medium-Germanic dialect.

Soon - and

not just for the issue of the drying-oil agent - the Strasburg manuscript became

the prototype of artistic techniques proposed in Northern Europe around 1400;

likewise Cennini’s Book of the art took a similar role with regards to Italy.

While lost, the text has therefore become part of a very small group of reference

manuscripts for the history of arti techniques, such as the texts of

Heraclius, the De diversis artibus of Theophilus and the Mappae clavicula.

De-constructing for re-constructing

In order to

explain what constitutes the novelty of the Neven issue, we are forced to open

a parenthesis on the method. The authoress did not want to simply stick to the information

acquired on the manuscript. First of all, she questioned the

"paradigmatic" part of the text as a representative of all the techniques

from Northern Europe. The reality is different, and speaks of hundreds of

texts, each with its own specificity, depending in turn from different

practices applied in different geographical areas. Therefore, she investigated and

identified specificities one by one. Sylvie Neven belongs to a generation of

historians of art techniques which has learned to analyse the particular always

having in mind the big picture. One of these scholars (Mark Clarke) was

responsible for the drafting, in 2001, of a formidable repertoire (The Art of All Colours. Mediaeval Recipe

Books for Painters and Illuminators, also published by Archetype) where are

scrutinized and classified over 400 medieval manuscripts written until 1500.

When the

search field takes this size is inevitable to refer to electronic resources. Ms

Neven is part of several projects for the registration of manuscript materials.

I am quoting, among others, the Colour Context Website, under the auspices of

the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, in which more than 600 recipes

were transcribed, up to the Theodore de Mayerne’s years (in short, until the

beginning of 1600).

|

| Source: https://arb.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de/ |

As you can

imagine, the critical point, when using these tools, is not so much to find

data, but to scrutinise them according to uniform criteria. One is invariably

faced with texts written in several languages, with materials and pigments

indicated with different terminologies, with sometimes very high, and sometimes

entirely superficial, analytical levels. All these texts, however - being part

of that Fachliteratur which was

mentioned at the beginning - have one thing in common: to be arranged through

recipes, which are sometimes only one line, sometimes a whole page long. The

fundamental task of those who work in the sector is to identify and separate

every single recipe from each other. The normalization of a text entails some

basic rules, the first of which is the separation of recipes related to each

other. In fact, it often happens that a process of realization of a given

material is immediately followed by the indication of a variant. In this case, the

two recipes are to be separated. The scholar proceeds, in short, in a work of

deconstruction of the text until the most elementary level is reached, and that

level is precisely the recipe in the etymological sense of the word (from the

Latin recipere – to take): “the

recipe appears as ‘the shortest element in which the text could ultimately be decomposed’

(Halleaux, 1979: 74)… This definition could be refined by adding that the

recipe is the smallest independent

element into which the text could be divided. In fact, a recipe could be seen

as an independent text in itself and could therefore be dissociated from its

original recipe collection and introduced into the pages of another manuscript.

For this reason, it may be argued that the format of the recipe could be

considered as the structural unit common to several disciplines embedded within

the manuscripts belonging to the Fachliteratur”

(p. 55)

Once the

de-composition has been implemented, it is of course to be checked whether

other manuscripts provide sequences of "parallel recipes" with

respect to the specimen covered (in this case the Strasbourg Manuscript) and then to determine whether there is a Tradition,

constituted by more texts, which presents its contents. “Numerous recipes show similarities in their lexicon in

describing a similar procedure.

However, in order to be identified as part of the Strasbourg Tradition, a

recipe would also need to be similar in terms of syntax. Syntactical

similiarities would imply textual parallels

that were sufficiently clear in order to attest the same textual origin(s). Therefore,

parallel recipes probably derive from

the same textual source and should be distinguished from recipes that are similar in their technical content (Clarke

2011: 17-18)" (p. 26).

The Strasbourg Tradition

Mind you,

some scholars had already pointed out to the similarity between the Eastlake

exemplary and other manuscripts, but this had not led to the systematic study

of the Tradition. “The detection and defining of a textual and ‘technical’

tradition of recipe collection, as undertaken in the present study, could not

have relied on serendipity – it resulted from the application of systematic

research and analysis" (p. 27). “For the purpose of this study, only the

recipe collections sharing at least 10 instructions in common were taken into

account. From the initial large corpus of more than 600 examples, a smaller and

clearer corpus of manuscripts belonging to the Strasbourg Tradition was

defined. New textual evidence was discovered and the ‘Strasbourg Tradition’ now

corresponds to a group of 15 manuscripts" (p. 29).

In sum, we

must get used to thinking of two levels: on the one hand the single copy of the

Strasbourg Manuscript produced by

Eastlake and, second, 15 manuscripts that make up the Tradition; starting from

here, we need to consider whether the examination of the Tradition may shed

light on the single specimen.

The book

examines which elements the manuscripts of the Tradition share. In general, it

can be noted that the texts in question are all originating in southern

Germany, and written mainly in three dialects: High Franconian, Bavarian and Alemannic

(the latter is the case of the Strasbourg

Manuscript in the sense strict). There are only few exceptions. We recall

among them the Vossianus Chymicus Octavo

6 (p. 59), now preserved in Leiden, because we will mention it later. Mostly

prepared in religious centres (typically in monasteries), all manuscripts

appear as composite texts, in a twofold sense. First, they are bound together

with other texts of Fachliteratur which

are mainly concerned with provisions of a medical nature; secondly, the

individual sections devoted to artistic recipes still seem to be a mix of

recipes copied from other texts, of recipes provided for the occasion by local

artists and of inputs collected (and sometimes even experienced) by those who

wrote them.

The

manuscripts, in short, share complete sequences of "parallel

recipes". In certain situations some sequences may appear more complete

than others. In particular, the 15 manuscripts of the Strasbourg tradition share

five sequences of recipes; two of them are common to the Strasbourg Manuscript in

the strict sense and the other documents. Sequence A has to do with the

preparation of colours and materials for illumination; Sequence B provides

guidance on how to temper pigments and to lay tints especially on wood.

Sequence A

is demonstrated in the specimens that are considered to be (on a palaeographic

basis) the oldest. However, it is fair to note that, if the absolute oldest

appears to be the Manuscript Strasbourg

(whose dating Sylvie Neven assesses to be before 1412, on the basis of

information found in archives on Andrew of Colmar’s life - see p. 56 - ), the

most complete sequence is presented in other manuscripts, especially the Vossianus Chymicus Octavo 6 and the Amberger Malerbuch (a transcript of the Vossianus Chimicus Octavo 6 is also

provided in Appendix I). How is it possible that subsequent manuscripts would present

more complete sequences? Manifold assumptions can hold. One thing appears

certain: the Strasbourg Manuscript was

not the prototype of Tradition; in fact, it displays textual shortcomings (indeed

empty spaces, because the copied text was not interpretable) that can be completed

through the use of the Vossianus. There was therefore an even earlier

prototype. Having understood it, a lot can have happened: both the Strasbourg Manuscript

and the Vossianus may be copies, relative to the sequence A, from the same

prototype, and the editor of the Strasburg Manuscript may have decided to

leaving out a part of it. However, it cannot be excluded that the process may

have been much more recent and the waiver of part of the sequence may have

occurred on the occasion of the copy which Eastlake ordered. It is to be noted,

however, that, even in the part which was not discarded, the succession of the

recipes in the Eastlake copy is different from that of all other traditional

manuscripts, a clear sign that the copy was not faithful but coincided with an arbitrarily

rearrangement of the available material. Finally, one should also note that the

length of the Eastlake copy appears to be different from two descriptions of

the burnt manuscript, which were discovered by Neven; with respect to them, the

text appears shorter and arranged in a different way than the original.

Whatever may

have happened, the Strasburg Manuscript

clearly appears to be a transcript deriving in part from the copy of (at least)

two previous texts: on the one hand a treatise on miniature, as precisely shown

by Sequence A, which was later copied in many other witnesses of the Tradition

and, on the other hand, a second treatise on painting (Sequence B) which

instead appears to have had a much lower circulation and be shared with only

two other manuscripts: one called Colmarer

Kunstbuch and the Bamberger Malerbuch.

Even in this case, the wider witness of the sequence is not the Strasburg

manuscript, but the Colmarer Kunstbuch.

Besides the two sequences in question, also recipes exist which appear

sporadically in other manuscripts, as well as absolutely specific passages

which, for this reason, are called by the Latin term unica.

|

| The Mckell Medical Almanack in German, illuminated manuscript on parchment, Alsace, circa 1445, 12 leaves Source: https://www.liveauctioneers.com |

The new critical edition of the Strasburg Manuscript

Everything

we have said before justifies how Neven came to the conclusion, on the basis of

the texts of the Tradition, that the division of the Strasbourg Manuscript into three parts and ninety recipes, operated

by Berger, should be reviewed. First of all the recipes (for the above

described process of reduction to elementary units) become 114. Then, as part

of the manuscript, the author identifies seven different sections. However, it

should be immediately clarified: no shift, for whatsoever reason, in the order

of presentation of the recipes was operated. Rightly so, Ms Neven limits

herself to report - in her opinion - the original order of the prototype, which

was then historically modified, for many reasons.

Let us examine

all the seven sections (see pp. 39-44):

- Section I: corresponds to what, according to Berger, was the first (and short) part of the manuscript. It presents a short treatise attributed to Henry of Lubeck with guidance on techniques to paint in miniature;

- Section II: is the Sequence A which was discussed earlier. In the Strasburg manuscript, Sequence A is interrupted by two recipes that do not appear in any other text.

- Section III: it consists of only recipes 16 and 17, which are preparations for gilding. Between the two recipes the sentence is displayed: "This Andres von Colmar taught me." Berger closed the first part of the manuscript with the recipe 16 and started the second with the recipe 17. He attributed to Andrew of Colmar the paternity of twenty recipes, then moving on to the third party. According to Neven, things were different. In the Eastlake copy, recipes are proposed one after another without any spacing. The hypothesis is that the indication of Andrea of Colmar’s name was actually a note in the margin of the burned manuscript, placed between the recipes 16 and 17, and it was referred only to these two; in fact, thereafter, the text continues with prescriptions belonging to the Sequence A. The explanation by Neven seems absolutely plausible.

- Section IV: in substance, it is the least consistent of all, because it presents varied recipes that begin with an indication of the scribe that he would start providing instructions on painting techniques practiced in Lombardy (Eastlake thought it was not Lombardy, but London). Only a few of these recipes - which concern binders, translucent colours, preparation of the scrolls, gilding and various types of paint - also appear in other manuscripts of the Tradition and without being tied in sequence. The author supposes that these were contributions of the scribe. Within Section IV (which is then actually divided into two subsections IV a and IV b) appear the recipes of Sequence B. Allow me to still report an aspect which, in my opinion, remains unresolved: why Lombard techniques (or London ones, according to Eastlake)? We can assume that the anonymous scribe could have travelled there (or be born in those places).

- Section V: presents the recipes of Sequence B, common to the Colmarer Kunstbuch and the Bamberger Malerbuch.

- Section VI: it shows information relating to the preparation of supports not used in painting and illumination (for example, metal plating).

- Section VII: the last section includes recipes that appear to come from other sources. For instance, the names of Theophilus and Pietro di Sant'Audemaro have been suggested. In fact, the unique characteristic of this part is its heterogeneity, so that it includes also instructions for the preparation of soaps and a couple of magical prescriptions.

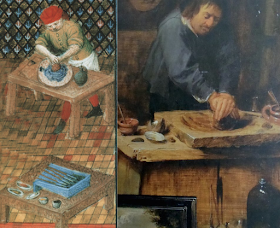

A literary text or a workshop recipe book?

The final

chapter of Neven’s work is devoted to an examination of what, ultimately, is

the main question every time one has to do with a medieval recipe book. Are we faced

with a text that was copied to pass a literary tradition and therefore was not

used in the workshops of craftsmen of the time? Or is it a collection of a purely

technical nature, arising directly from the knowledge of the artisan, and aiming

at the education of pupils? The topic has been discussed for more than one

century. Neven proposes theses for and against both alternatives and,

ultimately, already at p. 4, provides the answer referring to Mark Clarke’s

teachings: since the two types, in substance, coexisted, we need to manage distinguishing

today the literary and the teaching texts. The analysis has to be all over the

field, starting right from the appearance of manuscripts, and when it came down

to us: some manuscripts, such as the Bamberger

Malerbuch, appear written in an orderly and refined form, embellished with

titles and headings written in red. It is difficult to assume that these texts

were intended to be used near a furnace, and it is simpler to think that they

were intended for a scholar context. On the other hand the Trierer Malerbuch (we are talking about another manuscript

belonging to the Tradition of Strasbourg) looks much more unkempt and messy,

with the interpolation of subsequently written recipes among the spaces left empty

(see pp. 63-68).

The same

could be said about the scribes. Not always (in fact, hardly ever) one is able

to figure out who made the copy; many inconsistencies in the texts could hint

to the technical unpreparedness of those who drafted the copy (in the end, it

is what could have happened with Cennino Cennino’s Libro dell'arte, whose oldest copies reaching us was carried out in

the Stinche prison in Florence in

1437). And, nevertheless, one could not explain the recipes - which do exist -

in which writer's contributions are presented. Nor can it be ignored that in

some situations we know the name of the extensor. It is the case, for example, of

the Liber illuministarum (yet another

witness of the Strasbourg Tradition), extended by Konrad Sartori, known not

only for being the librarian of the monastery of Tegernsee (Bavaria), but also

a copyist and illuminator (see. p. 63).

The specificity of the Strasburg Manuscript

In this

delicate game between literature and technique, it is of course of particularly

importance the analysis of the specificity of a text. These particularities appear

to be linked to the territory in which the text itself was produced. In the

case of the Strasbourg Manuscript,

then, it was the area roughly comprising Alsace and Bavaria (once again, the

authoress denies the possibility that the manuscript can be taken on the

prototype of all Northern European techniques). A peculiarity is without doubt

constituted by the oil drying agent for panel painting, already highlighted

by Eastlake in 1847. Neven identifies a second specificity in the use of anthocyanins,

or water-soluble pigments of plant origin from poppies, cornflowers and

blueberry plants. Since they are particularly sensitive to the Ph, it was believed that, for this reason, anthocyanins were used

exclusively for the clothing and textile colours, while the Strasburg Manuscript certifies their use

in painting and miniature. The last pages of the work - as well as Appendix II

- are dedicated to laboratory experiments that aim at studying the production

of anthocyanin pigments, by following the recipes provided in the manuscript,

and find traces in artefacts of the first 1400s in the Strasbourg area, which

have come down to us.

A further

proof, if ever there was a doubt, of how wide the spectrum of knowledge is of

which historians of artistic techniques must be equipped with, ranging from palaeography

to chemistry, from history to the knowledge of ancient dialects and philology; this

would almost induce us to say that a good historian of artistic techniques is

not a specialist, but rather a new (perhaps the last) humanist.

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento