CLICK HERE FOR ITALIAN VERSION

Sebastiano Serlio à Lyon. Architecture et imprimerie

[Sebastiano Serlio in Lyon. Architecture and printing]

Volume 1. Le Traité d’Architecture de Sebastiano Serlio. Une grande entreprise éditoriale au XVIe siècle

Edited by Sylvie Deswarte Rosa

Part Three

Go to Part One

Dutch:

Translation of Book IV (Generalen Reglen der Architecturen – General rules of architecture): Antwerp, 1539;

Translation of Book III (Die alder vermaertste Antique edificien – The most renowned old buildings), Antwerp, 1546;

Second edition of the translation of Book IV: Antwerp, 1549;

Translation of Books I, II and V, published posthumously in Antwerp in 1553 by the widow of Pieter Coecke van Aelst;

Second edition of the translation of Books I, II and V, always by the widow (Antwerp, 1558).

French:

Translation of Book IV: Antwerp, 1542;

Second edition of the translation of Book IV: Antwerp, 1545;

Translation of Book III: Antwerp, 1550;

Third edition of the translation of Book IV: Antwerp, 1550.

German:

Translation of Book Four (translation by Jacob Rechlinger in Augsburg): Antwerp, 1543;

Second edition of the translation of Book Four (translation by Jacob Rechlinger in Augsburg): Antwerp, 1558.

Edited by Sylvie Deswarte Rosa

Part Three

|

| The Dutch pirated edition of Serlio's Book IV by Pieter Coecke van Aelst (1539) Source: http://architectura.cesr.univ-tours.fr/Traite/Auteur/Coeke.asp?param= |

We continue exhibiting and explaining the contributions published within the work entitled Sebastiano Serlio à Lyon (Sebastiano Serlio in Lyon).

Anvers: Les premières traductions du traité d’architecture de Serlio (The first translations of Serlio’s Treatise of architecture):

- Krista De Jonge. Les éditions du traité de Serlio par Pieter Coecke van Aelst (The editions of Serlio’s Treatise by Pieter Coecke van Aelst).

The name of Pieter Coecke van Aelst is closely linked to that of Sebastiano Serlio. It is true that Pieter was a painter of a respectable fame, but there is no doubt that his name is above all known for having translated Serlio and thus for having disseminated the prescriptions of modern "antique-oriented" architecture to Northern Europe. This is not - mind you - an opinion expressed only centuries afterwards, but an assessment formulated already a few years after his death. Coecke van Aelst (born in 1502) died in Antwerp in 1550, and in 1572 Domenico Lampsonio dedicated to him an effigy in his Ritratti di pittori celebri fiamminghi (Portraits of famous Flemish painters) (see Domenico Lampsonio, Portraits of famous Flemish painters in From van Eyck to Brueghel. Writings on arts by Dominicus Lampsonius, pp. 96-97). Here are the lines that Lampsonius wrote at the bottom of the portrait: "Pieter, you were a painter, but not only a painter, / for, with your art, you make your Aelst famous world-wide: / a great skill comes / to those who have the task of building beautiful homes. / Serlio has taught it to Italians: you, Serlio’s translator in two languages / are teaching it to the Flemish and to the French."

Let me be clear: Pieter was indeed Serlio’s translator, but a ‘pirate’ one, i.e. the author of editions which Serlio never approved, so that the latter repeatedly threatened to pursue the former in courts. Of course, the first book to be illicitly translated is Book IV, published by Serlio in Venice in 1537 and published in Dutch in Antwerp in 1539; Serlio’s name appears only in the Notice to the reader and in the colophon.

The first translation in French (always of Book IV) was dated 1542: here Serlio - who lives in France - is only mentioned in the colophon. The first German translation was dated 1543 and Coecke, who certainly did not have any scruple to hide the name of the Bolognese architect, this time felt necessary to report that the translation is not his own, but by Jacob Rechlinger from Augsburg (in this sense, it is correct what Lampsonio said: Pieter translated Serlio in two languages, but - we might add - took care of the edition of the work in three languages). When, in 1545, the Bolognese architect published a bilingual, Italian and French, edition of the Books I and II of the Treaty, with a translation by Jean Martin, he informed the audience that soon also a French version of the Books III and IV would be published, always a work by Jean Martin. In short, it was the announcement of an "official" edition in French, against the pirated editions by Pieter (however, an official edition that was never produced). Moreover, Serlio threatened to call the unauthorized translators accountable to justice of the King of France.

Now, it's just obvious that such a threat could only make Pieter smile, as he lived in Antwerp, i.e. under the authority of that Charles V, who had already imprisoned the French king Francis I in the previous years, and whose empire was the de facto hegemon in Europe (except for France and England). All threats by Serlio remained therefore ineffective and Coecke van Aelst went on quietly with his work of translation.

|

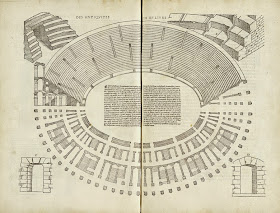

| The Verona Arena in the pirated French-edition of Serlio's Book III by Pieter Coecke van Aelst (Antwerp 1550) Source: http://architectura.cesr.univ-tours.fr/Traite/Images/LES1744Index.asp |

It is useful to list the many issues promoted by the painter and architect from Aelst, distinguishing them by language.

Dutch:

Translation of Book IV (Generalen Reglen der Architecturen – General rules of architecture): Antwerp, 1539;

Translation of Book III (Die alder vermaertste Antique edificien – The most renowned old buildings), Antwerp, 1546;

Second edition of the translation of Book IV: Antwerp, 1549;

Translation of Books I, II and V, published posthumously in Antwerp in 1553 by the widow of Pieter Coecke van Aelst;

Second edition of the translation of Books I, II and V, always by the widow (Antwerp, 1558).

French:

Translation of Book IV: Antwerp, 1542;

Second edition of the translation of Book IV: Antwerp, 1545;

Translation of Book III: Antwerp, 1550;

Third edition of the translation of Book IV: Antwerp, 1550.

German:

Translation of Book Four (translation by Jacob Rechlinger in Augsburg): Antwerp, 1543;

Second edition of the translation of Book Four (translation by Jacob Rechlinger in Augsburg): Antwerp, 1558.

The fortune of the Dutch edition by Coecke van Aelst was significant. In 1606, the first edition in one single volume of the five books was produced in Amsterdam, based on the text and illustrations provided by Pieter. The Dutch edition was later on translated into English in 1611 and would be in fact the only version known in the English-speaking world until the critical edition of Vaughan Hart and Peter Hicks in 1996 (see the third part of the present work, devoted to the impact of Serlio’s Treaty).

The architectural interests of Coecke van Aelst went beyond Serlio’s translation. It is to be remembered that he was also the author of a treatise entitled Die inventie der colommen (The invention of colums), published in 1539, and of a Livret de l'Entrée du Prince Philippe à Anvers (Booklet of the arrival of Price Philippe in Antwerp) (Antwerp, 1550), together with Cornelis Grapheus. On it, see below Krista De Jonge, Le livre d'architecture aux Pays-Bas au XVIe siècle (The book on architecture in the Low Countries in the sixteenth century).

- Krista De Jonge. L’édition de la traduction néerlandaise du Livre IV par Pieter Coecke van Aelst à Anvers en 1539 (The edition of the Dutch translation of Book IV by Pieter Coecke van Aelst in Antwerp in 1539);

- Krista De Jonge. La deuxième édition en néerlandais du Livre IV chez Pieter Coecke van Aelst à Anvers en 1549 (The second edition in Dutch of Book IV by Pieter Coecke van Aelst in Antwerp in 1549);

- Krista De Jonge. Les éditions de la traduction française du Livre IV par Pieter Coecke van Aelst à Anvers en 1542 et en 1545 (The editions of the French translations of Book IV by Pieter Coecke van Aelst in Antwerp in 1542 and in 1545);

- Krista De Jonge. L’édition de la traduction allemande du Livre IV par Jacob Rechlinger chez Pieter Coecke van Aelst à Anvers en 1542 [1543] (The edition of the German translation of Book IV by Jacob Rechlingerat at Pieter Coecke van Aelst, in Antwerp in 1542 [1543]);

- Krista De Jonge. L’édition de la traduction néerlandaise du Livre III par Pieter Coecke van Aelst à Anvers en 1546 (The edition of the Dutch translation of Book III by Pieter Coecke van Aelst, in Antwerp in 1546);

- Krista De Jonge. L’édition de la traduction française du Livre III par Pieter Coecke van Aelst à Anvers en 1550 (The edition of the French translation of Book III by Pieter Coecke van Aelst, in Antwerp in 1550).

Tolède: Traduction en castillan des Livres II, III et IV du Traité d’architecture de Serlio

- Agustín Bustamante, Fernando Marías. La reception du traité de Serlio en Espagne (The reception of Serlio’s treatise in Spain)

In 1552, the Spanish architect Francisco de Villalpando published (in one volume) the first translation in Castilian of Books III and IV by Serlio, dedicating the work to Prince Philip, the future Philip II. The publisher was Juan de Ayala, operating in Toledo. Also the Iberian Peninsula rewarded the work of the Bolognese architect with his interest, so much so that, after the death of Villalpando (1561), there were other two editions, respectively in 1563 and in 1573, which essentially did not differ particularly from the first translation. However, the other books of Serlio will be never translated into Spanish (until recently). It is known that Villalpando also worked to translate Books I and II, and it should be noted that a manuscript with the (incomplete) translation of Book II is located at the National Library in Madrid, with signature Ms. 9177. While probably dating to the mid-1500s, it is however not due to Villalpando, both for calligraphic reasons and technical lexicon.

- Agustín Bustamante, Fernando Marías. Les éditions de la traduction espagnole par Francisco de Villalpando, Tercero y Quarto Libro de Architectura, chez Juan de Ayala à Tolède en 1552, 1563 et 1573 (The editions of the Spanish translation by Francisco de Villalpando, Book III and IV, at Juan de Aala in Toledo in 1552);

- Agustín Bustamante, Fernando Marías. L’imprimeur Juan de Ayala (The printer Juan de Ayala);

- Agustín Bustamante, Fernando Marías. Le manuscrit de la traduction espagnole du Livre II (The manuscript of the Spanish translation of Book II)

Bâle: Première édition en allemand des Livres I à V de Serlio

- Hubertus Günther. L’édition en allemand des Livres I à V chez Ludwig König à Bâle en 1608 et 1609 (The German edition of Books I to IV at Ludwig König in Basel in 1608 and 1609).

As it is well known (see also Krista De Jonge. Les éditions du traité de Serlio par Pieter Coecke van Aelst – The editions of the Treaty of Serlio by Pieter Coecke van Aelst) the first Dutch edition of Serlio’s Books from I to IV was made in one volume in Amsterdam in 1606. It was printed by Cornelis Claeszoon, who did not merely reproduce faithfully the translation of the painter and architect of Aelst, but also procured the original wood used for the etchings by Coecke and reused them for the iconographic apparatus of his edition.

|

| A plate from the German translation in Basel (1608-1609). Book II: perspective Source: http://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/serlio1609 |

Between 1608 and 1609 the first German translation of Serlio’s five books was published in Basel, by Ludwig König. In fact, there was already a German translation, however of Book IV only (a work by Jacob Rechlinger promoted by Coecke, published first in 1543 and then in 1558). However, this time, the anonymous translator (probably König himself) arranged to provide a new translation of the Book IV also, basing his work on the issue in full Claeszoon of 1606. There was certainly, then, a commercial agreement between König and Claeszoon, since the former was authorised to use the original woods by Coecke van Aelst for his edition, woods already recovered by Claeszoon. A similar commercial operation was repeated in England, two years later, for the first English translation of the Books I to V (see Vaughan Hart and Peter Hicks. L’édition en anglais des Livres I à V chez Robert Peake à Londres en 1611 - The English edition of Books I to V at Robert Peake in London in 1611).

Londres: L’édition en anglais des Livres I à V de Serlio (The English Edition of Serlio's Books I to V)

- Vaughan Hart, Peter Hicks. L’édition en anglais des Livres I à V chez Robert Peake à Londres en 1611 (The English edition of Books I to V at Robert Peake in London in 1611).

Just like the 1608-9 German edition in Basel, also the first English translation of the Books I to V of Serlio’s Treaty, financed by Robert Peake and published in London in 1611, is based on the version provided by Cornelis Claeszoon in Amsterdam in 1606, which was in turn based on the pirated editions published by Pieter Coecke van Aelst (see Krista de Jonge. Les éditions du traité de Serlio par Pieter Coecke van Aelst – The editions of Serlio’s Treatise by Pieter Coecke van Aelst). And also in this case, following a commercial agreement, the original wood of the Coecke editions are used, recovered by Claeszoon, which apparently Peake was permitted to make use of in exchange for money. It is however still to be proven that the translator was just Robert Peake.

|

| The front-cover of the 1611 English edition (Books I to V) Surce: https://archive.org/details/firstbookeofarch00serl |

THIRD PART – Antécédents et répercussions du traité d’architecture de Serlio (Precedents and repercussions of Serlio's Treatise of Architecture)

- Introduction: Sylvie Deswarte-Rosa. Antécédents et Répercussions du traité de Sebastiano Serlio: le mouvement inexorable de la théorie architecturale vers le Nord et vers l’Ouest (Precedents and repercussions of the Treatise of architecture of Sebastiano Serlio: the unstoppable dissemination of architectural theory towards North and West).

This paper introduces the third section of Sebastiano Serlio à Lyon. Architecture et imprimerie (Sebastiano Serlio in Lyon. Architecture and printing), a section dedicated to the antecedents and consequences of Serlio’s Treaty in Europe. It is recommendable to read it immediately after the general introduction of the work, also written by Deswarte-Rosa and entitled Le Traité d'architecture de Sebastiano Serlio, the œuvre d'une vie (The Treatise of architecture by Sebastiano Serlio, a life-time work - See Part One). The final part of that essay highlighted that Serlio had given a fluctuating image of his work and his thought in the books he wrote during his life. Not surprisingly, Ms Deswarte starts the present essay, by stressing that that the influence, which the Bolognese architect exerted in architectural circles by in the following years, reveals to be of a different nature; there are those who refers to Serlio as an orthodox interpreter of Vitruvian thinking (Books III and IV), but also those who recognizes the most innovative aspects in the mixtures of orders and styles presented in the subsequent books or in the amazing fantasy of which the Extraordinary Book is the fruit.

What seems indisputable is the extraordinary impact which Serlio had on architectural theory in the years to follow. Not surprisingly, Ms Deswarte-Rosa talks of an unstoppable dissemination of architectural theory from Italy to the North (France, Germany, the Netherlands) and to the West (Spain and Portugal). We believe it is necessary not to misrepresent the precise connotation of the term inexorable (unstoppable), which in this context must never be read in a deterministic way. The relentlessness of this reference is the product of a process that Serlio set in action, at least in principle, by imposing himself as an interpreter of modern antique-oriented architecture through the illustrated book, an extraordinary means of transmission of information for all those who had not personally experienced the experience of traveling to Italy; however, it is also a mechanism that bypassed Serlio and ended overwhelming him, when others plagiarized the work and in turn spread it without his consent. We are talking of course of Pieter Coecke van Aelst on the one hand and of Francisco de Villalpando on the other one. Essentially, they are both indifferent to Serlio’s claims, as they enjoyed the protection of the Emperor Charles V. So we should speak, more correctly, of a great influence by Serlio in Europe and by those who did not hesitate to plagiarize him.

The final part of the survey by Deswarte-Rose does not fail to point out how that "Architecture ... speaks first and foremost of society in its various social bodies, of religion and its mysteries, and celebrates the power better than any other art. In this perspective, the architecture is powerfully symbolic" (p. 339). To investigate the relationships between architecture (or, better, between architects) and power is certainly not a sterile attempt to interpret reality forcing it into a predetermined pattern. It rather helps to better explain why the fortunes of Serlio have been able to rise to so high levels in most of Europe and, on the other hand, to understand the reasons for their rapid decline in the following century.

Les Antécédents (The Precedents)

Trois éditions illustrées de Vitruve (Three illustrated editions of Vitruvius' treatise):

- Pier Nicola Pagliara. Le De Architectura de Vitruve édité par Fra Giocondo, à Venise en 1511 (The De Architectura by Vitruvius, edited by Fra Giocondo in Venice in 1511);

- Francesco Paolo Fiore. Le De Architectura de Vitruve édité par Cesare Cesariano, à Côme en 1521 (The De Architectura by Vitruvius, edited by Cesare Cesariano in Como in 1521);

- Pier Nicola Pagliara. Le De Architectura de Vitruve édité par les Gabiano, à Lyon en 1523 (The De Architectura by Vitruvius edited by Gabiano in Lyon in 1523).

Un roman et trois traités précurseurs (A Novel and three forerunning treatises)

- Martine Furno. L’Hypnerotomachia Poliphili de Francesco Colonna, à Venise chez Alde Manuce en 1499 (The Hypnerotomachia Poliphili by Francesco Colonna, in Venice at Aldo Manunzio in 1499);

- Mario Carpo. Le De Re Aedificatoria. Leon Battista Alberti et sa traduction française par Jean Martin, à Paris chez Jacques Kerver en 1553 (The De Re Aedificatoria. Leon Battista Alberti and its French translation by Jean Martin, in Paris at Jacques Kerver in 1553);

- Hubertus Günther. Underweysung der Messung, traité de geometrie d’Albrecht Dürer, publié à Nuremberg chez Koberger en 1525 (The Underweysung der Messung, The treatise of geometry by Albrecht Dürer, published in Nuremberg at Koberger in 1525;

- Yves Pauwels. Le traité des Medidas del Romano de Diego de Sagredo, à Tolède en 1526 et sa traduction française, à Paris chez Simon de Colines (The treatise of Medidas of the Roman by Diego de Sagredo, in Toledo in 1526 and its French translation, in Paris at Simon de Colines).

Les Répercussions (The Repercussions):

Italie (Italy):

- Sylvie Deswarte-Rosa. Le Libro appartenente all’architectura d’Antonio Labacco, à Rome en 1552 (The Book belonging to architecture by Antonio Labacco in Rome in 1552);

- Christof Thoenes. La Regola delle cinque ordini di architettura de Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola, à Rome en 1562 (The Rule of the five Orders of architecture by Giacomo Barozzi da Vignola in Rome in 1562);

- Louis Cellauro. Les éditions de Vitruve par Daniele Barbaro, à Venise chez Marcolini en 1556 et chez de’ Franceschi 1567 (The editions of Vitruve by Daniele Barbaro in Venice at Marcolini in 1556 and de' Franceschi in 1567);

- Frédérique Lemerle. Les Quattro Libri dell’Architettura d’Andrea Palladio, à Venise en 1570 (The Four Books of Architecture by Andrea Palladio, in Venice in 1570);

- Annie Regond. L’édition du traité d’architecture de Pietro Cataneo, à Venise en 1576 (The edition of the Treatise of architecture by Pietro Cataneo in Venice in 1576);

- Anna Bedon. Le Della Architettura de Giovan Antonio Rusconi, à Venise en 1590 (On Architecture by Giovanni Antonio Rusconi, in Venice in 1590)

- Frédérique Lemerle. L’Idea della Architettura Universale de Vincenzo Scamozzi, à Venise en 1615 (The Idea of Universal Architecture by Vincenzo Scamozzi, in Venice in 1615).

France:

- Yves Pauwels. Serlio et le vitruvianisme français de la Renaissance: Goujon, Bullant, De L’Orme (Serlio and French Vitruvianism in Renaissance: Goujon, Bullant, De L’Orme);

- Frédérique Lemerle. L’Architecture ou Art de bien bâtir de Vitruve, traduit par Jean Martin à Paris chez Jacques Gazeau en 1547 (The Architecture or the Art of proper edification by Vitruvius, translated by Jean Martin in Paris at Jacques Gazeau in 1547);

- Toshinori Uetani. Le manuscrit illustré du Premier Livre de l’Architecture de Vitruve, traduit par Jean Martin (The Illustrated manuscript of the First Book of Vitruvius, translated by Jean Martin);

- Mario Carpo. L’Architecture ou art de bien bâtir de Vitruve par Jean Martin, à Cologny chez Jean de Tournes en 1618 (The Architecture or the Art of proper edification by Vitruvius, by Jean Martin, in Cologny at Jean de Tournes en 1618)

- Frédérique Lemerle. L’édition lyonnaise des Annotations de Guillaume Philandrier sur Vitruve, à Lyon chez Jean de Tournes en 1552 (The Lyon edition of the Annotations by Guillaume Philandrier on Vitruvius, in Lyon at Jean de Tournes in 1552);

- Frédérique Lemerle. Notice sur l’édition lyonnaise des Annotations de Guillaume Philandrier (Considerations on the Lyon edition of the Annotations by Guillaume Philandrier);

- Bruno Tollon. L’Epitome de Vitruve par Jean Gardet et Dominique Bertin, à Toulouse en 1559 [1560] (The Epitome of Vitruvius by Jean Gardet et Dominique Bertin, in Toulouse in 1559 [1560]);

- Yves Pauwels. Les Nouvelles Inventions pour bien bastir de Philibert De L’Orme, à Paris en 1561 et Le Premier Tome de l’Architecture, à Paris en 1567 (The New Inventions of a proper edification, by Philibert De L'Orme in Paris in 1561 and the First Tome of the Architecture in Paris in 1567);

- Yves Pauwels. La Reigle generalle d’Architecture de Jean Bullant, à Paris en 1564 (The General Rule of Architecture by Jean Bullant, in Paris in 1564);

- Claude Mignot. Bâtir pour toutes sortes de personnes: Serlio, Du Cerceau, Le Muet et leurs successeurs en France. Fortune d’une idée editoriale (Building for all kinds of people: Serlio, Du Cerceau, Le Muet and their successors in France. Fortune of an editorial idea);

- David Thomson. Les trois Livres d’Architecture de Jacques Ie Androuet Du Cerceau, à Paris en 1559, 1561, 1582 (The three Books of Architecture by Jacques I Androuet Du Cerceau, in Paris in 1559, 1561, 1582);

- Françoise Boudon. Les Plus Excellents Batiments de France de Jacques Ie Androuet Du Cerceau, à Paris en 1576 et 1579 (The most excellent buildings of France, by Jacques I Androuet Du Cerceau, in Paris in 1576 and 1579);

- Sylvie Deswarte-Rosa. Serlio et Jacques Ie Androuet Du Cerceau dans le Recueil de Dessins de Camille de Neuville, à Lyon (Serlio and Jacques I Androuet Du Cerceau in the Collection of Drawings of Camille de Neuville, in Lyon);

- Henri-Stéphane Gulczynski. L’Œuvre de la Diversité des Termes de Hugues Sambin, à Lyon en 1572 (The Work on the Diversity of Terms, by Hugues Sambin in Lyon in 1572);

- Paulette Choné. Les Nouveaux Pourtraitz et Figures de Termes de Joseph Boillot, à Langres en 1592 (The New Portraits and reference Figures, by Joseph Boillot, in Langres in 1592);

- David Thomson. Le Premier Livre d’Architecture de Mauclerc, à La Rochelle, chez Jérôme Haultin en 1600 (The First Book of Architecture by Mauclerc, in La Rochelle, at Jérôme Haultin in 1600);

- Patricia O’Grady. Des Fortifications et Artifices. Architecture et perspective de Jacques Perret, à Paris en 1601 (On fortifications and innovations. Architecture and perspective, by Jacques Perret, in Paris in 1601);

- Claude Mignot. La Manière de Bâtir pour toutes sortes de personnes de Pierre Le Muet, Paris en 1623 (The Manual on how to build, for any kind of people, by Pierre Le Muet, in Paris in 1623).

Pays-Bas (Low Countries):

- Krista De Jonge. Les livres d’architecture aux Pays-Bas au XVIe siècle (The Books of Architecture in the Netherlands in the sixteenth century);

- Krista De Jonge. Die Inventie der colommen de Pieter Coecke, à Anvers en 1539 (The Invention of columns by Pieter Coecke, in Antwerp in 1539);

- Krista De Jonge. Le livret de l’Entrée du prince Philippe à Anvers par Cornelis Grapheus et Pieter Coecke, à Anvers en 1550 (The Booklet of the Entry of Prince Philip in Antwerp by Cornelis Pieter Coecke Grapheus, in Antwerp in 1550);

- Krista De Jonge. L’Architectura de Vredeman de Vries, à Anvers en 1598 (The Architectura by Vredeman de Vries, in Antwerp in 1598);

- Annemie De Vos. Le Premier Livre d’Architecture de Jacques Francart, à Bruxelles en 1617 (The First Book of Architecture by Jacques Francart, in Bruxelles in 1617).

Allemagne (Germany):

- Hubertus Günther. La théorie de l’architecture en Allemagne à la Renaissance (The theory of architecture in Germany during Renaissance).

The author shows that, at the origin of the German architectural theory, there are mechanisms very similar to those that were manifested in Italy in almost the same years: "the requirement to base science and art on theoretical principles, and to put these principles in writing, in order to provide clear and communicable definitions "(p. 496). It is worth remembering "the two books on building Gothic pinnacles and gables by Hans Schmuttermayer (around 1486) and Matthäus Roriczer (1486). Around 1500, Lorenz Lechner, basing himself on the most ancient rules, wrote a treatise on the regular disposition of churches. This text, copied many times, was never published" (ibid). These were years in which the German capacity to construct buildings (particularly churches) was also highlighted by Italian humanists. It matters little that the "modern" architecture, on which we are talking about, is actually the late Gothic and then we are moving in a field other than that of modern "antique-oriented" architecture that is proposed in Italy. The dichotomy, in fact, is much less clear than you might believe, if you think, for example, to the importance attributed by Caesar Cesariano to Milan's Cathedral, in his translation of Vitruvius. What really distinguishes the late Gothic theoretical writings from the Italian contemporary treaties is the absence of a cultural and humanistic background and the strong emphasis on the practical aspects of the subject. All this, of course, only until Dürer and not just his treatise on fortification, but also the Underweysung der Messung, where for the first time the symbol topic of classical architecture - namely that of the column and orders - is addressed in Germany (actually, Dürer talks about one order of columns, that the creativity of the architect can vary within certain limits).

The theme of the column marks, even from a theoretical point of view, the beginning of the dissemination of classical "antique-oriented" architecture in Germany (and the decline of the late Gothic). In this context, the forties of the 1500 saw the release of basic texts; on the one hand, the first German translation (in 1543) of Book IV of Serlio, on the other hand the works of Walther Hermann Ryff. Ryff (or Rivius, if you prefer) first published a Latin translation of Vitruvius (Strasbourg, 1543), then he published the Bericht und vast klare verstendliche unterrichtung zu rechtem verstandt der lehr Vitruuij (Report and most clearly understandable lesson on the right understanding of Vitruvius’ thinking) in 1547. Schlosser describes it as "the Bible of the late German Renaissance". Finally, Ryff prints the first German translation of Vitruvius. The translation is the edition provided by Cesare Cesariano in Como in 1521, but there is no doubt that, for clarity of presentation and terminology, the version of Ryff is superior to the Italian original. In this context, the reading and in-depth knowledge of Serlio have certainly affected the work of the German scholar. On Walther Ryff also see Hubertus Günther, Les ouvrages d’architecture publiés par Walther Hermann Ryff, à Nuremberg en 1547 et 1548 (The architectural books published by Walther Hermann Ryff, in Nuremberg in 1547 and 1548).

|

| A plate of the French translation of Hans Blum's Quinque colomnarum exacta descriptio (Antwerp 1551) Source: http://architectura.cesr.univ-tours.fr/Traite/Images/II38910cIndex.asp |

If the theoretical work following Ryff probably falls short of what, for example, happened in France at that same time, we cannot be silent about the extraordinary publishing success known by Hans Blum and his Quinque colomnarum exacta description (Exact description of the five columns), whose first edition, in Latin, was published in Zurich in 1550. It is a very simple work in itself, presenting orders with no special comments, and without any examples of antiquity or any inclination to exegesis of the Vitruvian text, but providing an iconography of extreme clarity and usability; in fact, the “invention" by Serlio (the architecture book explicated with images) is taken to extremes and becomes a library of images for practical-didactic use with very short texts. The success of Blum - as mentioned - was enormous; the first French translation dates back to 1551 and the first German one is dated 1555; the work of Blum was the first work of architectural theory to be translated into English (in 1601). Only in Italy the influence of the writing was altogether modest - there were no translations in our language - and the fact it is easy to be understood, when you consider that, in substance, the peninsula had produced a work inspired by similar models, with the Regola delli cinque ordini d’architettura (Rule of the five orders of architecture) by Vignola.

- Hubertus Günther. Les ouvrages d’architecture publiés par Walther Hermann Ryff, à Nuremberg en 1547 et 1548 (The architecture works published by Walther Hermann Ryff, in Nuremberg in 1547 and 1548);

- Hubertus Günther. Les colonnes vitruviennes du Maître W.H. H (The columns of Vitruvius by Master W.H.);

- Hubertus Günther. Le livre des ordres de Hans Blum, à Zurich en 1550 (The book of the Ordes by Hans Blum, in Zurich in 1550);

- Hubertus Günther. L’Architectura de Wendel Dietterlin, à Nuremberg en 1598 (The Architectura by Wendel Dietterlin, in Nuremberg in 1598).

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento