Max Klinger

Malerei und Zeichnung (Painting and Drawing)

Part Two: Two Separate Genres of Visual Art

(Review by Francesco Mazzaferro)

[Original version: January 2015 - New Version: April 2019]

Go back to Part One

|

| Fig. 11) The seventh edition of Drawing and painting, included in the very famous series of Insel Bücherei in 1919 in Berlin |

The writing

Painting and Drawing has a peculiar

story. Published in 1891, it was reprinted several times - as already mentioned

– in the early twentieth century. However, going carefully through the very

complete bibliography on Klinger published in 2008 [42], I discovered that the

writing – although very popular - was not specifically studied by scholarship.

Several monographs on Klinger were published and some of them included a few pages

of the pamphlet. However, a specifically addressed analysis on the text was

lacking, with one exception: a successful essay in 1917 by the poet Ferdinand

Avenarius – director of Der Kunstwart,

a magazine on art, music and literature - entitled "Klinger as a poet" [43] (mainly in the sense of creator) which

was however still at the border between critical analysis and eulogy of artist.

In that essay Klinger is cited, once again - the last time, perhaps -, as the

major artist of his time.

Critical scholars have dedicated specific attention

to the pamphlet only in recent decades. In Germany, one may quote (after the

excellent introduction by Annaliese Hübscher to the edition published by Reclam

Leipzig in 1985 [44]) an essay by Felix Billeter [45] in 1998, documenting the

genesis of the writing in great philological detail (with interesting photos of

the original manuscripts), and a recent contribution by Evelina Juntunen, who

interprets the series of etchings entitled "The Tent" in the light of

the text [46].

In the same

years, two British scholars have devoted significant writings to Painting and Drawing: Marsha Morton

(1995) [47], who discusses in detail the philosophical-literary reasons of the

text, and Elizabeth Pendleton Streicher [48] (1996), showing great interest in

describing the relationship of the work with the culture of the time and to

assess the reception of its contents. In Italy Painting and Drawing has been studied by Michele Dantini in 1998,

in an essay entitled "A comparison between the arts"; moreover, ample

space to the text of Klinger was devoted in the catalogue of the retrospective

dedicated to the artist, held in Ferrara in 1996. Dantini puts the pamphlet by

Klinger in relation to other theoretical works devoted to graphic art, edited

in France since the middle of the nineteenth century; this is an important

opportunity to analyse the links between French and German art.

Painting and drawing: naturalism and neo-idealism

The text is a

pamphlet of 46 pages, in the 1891 edition. A short and well-structured text,

which can be easily read [49]. A writing that was not drafted to be a treaty,

but as text supporting a specific thesis, which fits into the aesthetic

discussion of those decades. It aims in particular at showing that, since the

invention of printing, each artist had the possibility of going along two

alternative paths for art creation: painting and drawing. This allowed artists

to present themselves to the public in two versions: pictorial naturalism and

graphical neo-idealism. Painting and drawing are in fact both complete art

forms, which have different characteristics, merits and drawbacks, and therefore

allow the artist to pursue different goals: painting celebrates the beauty of

nature, while drawing allows the artist to highlight his subjective view of the

world (Weltanschauung), including his

most intense feelings. The discovery of printing, and therefore the possibility

of reproducing and disseminating any graphical work, however, has resulted in

the disappearance of any hope of returning to Gesamtkunst (i.e. total art), until new technological means are

found. The dichotomy between painting and drawing is objective, because it is

technological: painting is dominated by the colour, drawing by black and white.

Only the future discovery of new materials eliminating this difference will

lead to recovery in the future of Gesamtkunst.

The genesis of Painting and Drawing

The first

references to this thesis already appeared in the Journal of Klinger, published

in 1925 by Hildegard Heyne [50]. To the "Relationship between painting and

drawing" are devoted four pages dated November 1883 [51]: we are in the

first phase of the stay in Paris, which began in summer 1883 and was due to

finish three years later [52]. As written by Michele Dantini, upon his transfer

from Berlin to Paris, the young Klinger - which had already produced six themed

series of etchings and prepared many drawings for the later ones – intended

to extend his art creation from drawing to painting. "In the summer of

1883, when he decided to leave Berlin for Paris, it is painting that attracted

him to the French capital, and in particular the possibility to freely exercise

the study of the nude en plein air.

The Treaty which he is about to write will not establish then drawing, etching

or engraving as its exclusive scope of action; on the contrary, it will

summarize experiences and beliefs, display knowledge and familiarity, and will surely

re-launch Klinger as master of graphic, but only in preparation to something

more." [53]

Hildegard Heyne has analysed the archive of

Klinger in Naumburg and Leipzig [54] and found a notebook that includes a first

draft of Painting and Drawing dating

back to 1885 [55], an undated intermediate version and the handwritten text

drafted in Rome in 1890, coinciding with the first edition of 1891. So the

theoretical reflection of Klinger began in 1883 (Paris pages of the Journal),

was crystallized in 1885, had intermediate stages and ended in Rome, where

Klinger had moved because attracted by the ancient art, but above all by the

desire to expand his art to sculpture [57]. Some of his most important

paintings, rich in quotations from Renaissance, date back to the Roman period (The blue hour; Pietà; Crucifixion); the same

applies to the series of etchings titled "Fantasia on Brahms”. The Blue Hour (a symbolist interpretation of

melancholy, inspired from French impressionism) is considered by many to be the

most successful of all his paintings.

The reasons for a reflection on painting and drawing

It is Marsha Morton, in her already

mentioned essay [58], to explain the reasons for the reflection of Klinger.

There are at least three of them. One is the justification of his artistic

work, the second the state of graphic art in Germany until that moment and the

third the German debate on aesthetics at his time.

First: Klinger

wishes to broaden his area of interest from graphics to painting and sculpture;

at the same time, he is worried that his audience (especially the admirers of

his etchings) can have remained puzzled by his first attempts, starting with

the frescoes that he has already performed at Villa Albers years before. The

public might not have been sufficiently alerted, in his opinion, that drawing

and painting have necessarily different characteristics. About this he had

already written a long letter just to Albers, in February 1885. [59]

Second: the artist is concerned about the

state of knowledge on graphic art in Germany (both by artists and art critics

as well as by the public). In his view, the level of such knowledge is much

lower than in France, England and Belgium [60]. According to Klinger, the lack

of precise aesthetic criteria of differentiation between painting and drawing

is one of the main reasons for the crisis of German art in 1800: he is however

not convinced at all that there is a relentless decline of the creative German

spirit. In fact, he is sure that something should be done to correct that

mistake.

|

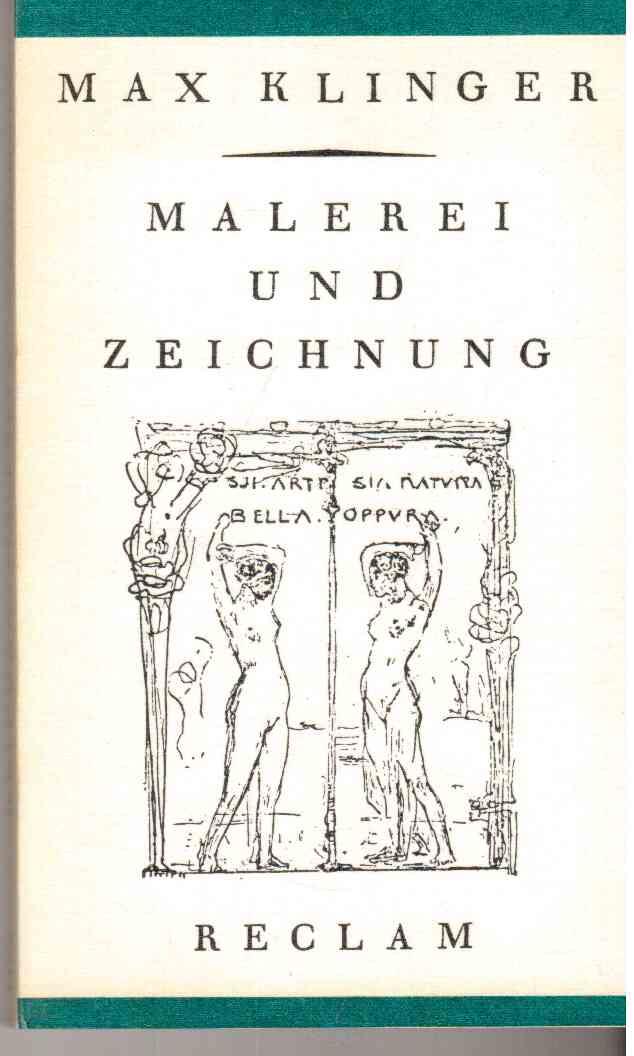

| Fig. 12) The eight edition, curated by Anneliese Hübscher and published by Reclam in 1985 in Leipzig |

Here is what Klinger wrote on this [61]:

“Sad to day, in the middle of this century German art made an attempt to apply

the aesthetics of drawings to painting. This in turn can be held largely

responsible for lack of formal awareness of the public today, which still has a

certain penchant for this ‘tradition’. That in itself could only have been

attempted by a nation with such a profound inclination as ours towards

poeticising. [Note of the editor: Klinger assigns to drawing the same evocative

features as poetry, and to painting that of representing nature].” [62] And

then he continues, just below: “Light, colour and form are absolutely the only

ground from which any picture, any decorative interior should spring. Giving up

anything of this, amounts to giving up everything. And the ensuing works are

generally nothing more than abstractions, which will fill the artist with

consternation rather than admiration. It is nonsense to cry ‘If Cornelius had

been able to paint…’.This is a premise that does not tally with what survives

of his work. Were that the case, he would never have made cartoons, but would

have composed and created quite differently. Colour has to be as carefully

thought out and worked out, in advance, as form, and simply adding colour to

his works would achieve as little, for instance, as the insipid colour

combination of Kaulbach. Cornelius concentrated his talents on rhythm and

imagination, and the undeniable power of his technique would only have been

diminished by colour and modelling. I would like to propose that Cornelius’

cartoons for the Camposanto pictures [note of the editor: the cemetery of

Berlin. Cornelius worked for twenty years, from 1844 to 1863, at a monumental

fresco cycle there, of which, however, he was able to produce only cartoons,

never starting the fresco] should be reproduced exactly as they are drawn, but

on a smaller scale, possibly 40 by 60 centimeters”. [63]

Third: the era of Klinger is marked by a

heated debate between naturalism and neo-idealism [64]. Klinger seems to seek for

a synthesis between the two positions. He assigns to painting the task to

imitate nature, and therefore takes the same position as naturalists and

impressionists. He adheres instead to the reasons of neo-idealism for graphics,

assigning to it the task of a deep reflection on the ultimate meaning of

reality.

Naturalism and neo-idealism in Germany

It is important to know that in the

aesthetic debate of the nineteenth century in Germany, as Marsha Morton

explains, there was a significant gap between naturalists and realists. The former

reproduced the nature telle-quelle,

in its appearance, without any elements of idealization; following the teaching

of Wilhelm Leibl, they focused their attention on scenes of rural and urban

life, that was not immune from displaying even the ugliness of nature (but also

social issues). The latter, instead, painted reality as they thought it should

ideally be and therefore they idealized it (also in the sense of a politically

correct representation of historical events, as in the case of the Historienmaler, the painters of

history). At the same time, the neo-idealists assigned a fundamental role in

the pictorial narrative to fantasy, poetry and emotion. German realism (it may

seem strange to those who come from an Italian perspective) joined then

neo-idealism and opposed both naturalism and impressionism. In fact, the

realists in Germany defined impressionism as unimaginative and not poetic; they

criticized its spiritual flattening and the absence of any deep feeling.

The pursuit of beauty and nature

(naturalism) is assigned by Klinger to painting. The expression of imagination

and feeling (neo-idealism) becomes instead the area of expertise of drawing, and

not any longer of painting. These may seem pedantic discussions, but reflect

cultural debates that were of great importance in the artistic culture of

Germany, during the whole period of activity of Klinger: the contrast between

form and content as the central point of the philosophy of art, and also of the

same art literature. Think of the essay by the sculptor Adolf von Hildebrand on

"The problem of form in the fine arts" (Das Problem der Form in der Kunst bildenden) of 1893 and to the

article "On the problem of the form" by Wassily Kandinsky, published

in the almanac of the Blue Rider in

1912 [65].

In terms of the philosophy of art, on the

one hand there were all those who Marsha Morton defines as 'scientific

formalists': Herbart and Fiedler "used scientific methods to establish

that aesthetics was the study of the relations of lines, planes, tones, and

colours" [66]. They were opposed by all those who - starting from the

tradition of Hegel - believed instead in a conceptual understanding, and not a

perceptive one, of art, based on both the associative phenomenon and on

empathy, and therefore on the role of symbols, mythology and fantasy [67].

The idea of Klinger to define the

relationship between painting and drawing is therefore also an attempt to find

a formula that allows the orderly coexistence of different schools of

aesthetics in the German world, with a priority given to form and narrative for

painting and contents and poetry for drawing. Marsha Morton sees this

compromise also as a direct result of the thinking of Arthur Schopenhauer,

Klinger’s favourite philosopher, and his vision of the world as a dialectical

relationship between the will (the drawing) and the representation (painting).

The purpose of painting

In the analysis of the purposes of painting

and drawing, Klinger establishes a direct link between technical instruments

and aesthetic purposes. The world of painting is that of the representation of

nature (the purpose) through shapes and colours (the technical vehicle) and –

by these means – the pursuit of beauty and harmony. "Its purpose is to

express the coloured, bodily world in an harmonious manner; even the expression

of force and passion must be subordinated to this harmony." [68]

The task of the artist is that of a pure creation, regardless of content: “Generating its effect entirely of its own accord, independent of space and surroundings, the appeal of the picture derives exclusively from the deployment and mastery of its wonderfully malleable material and contents, embracing the whole of the visible world and portraying it in all its manifestations with clarity and depth.” [69] And further on: “The magic of the picture lies in its ability to embrace and to see, to explore and relate to all that is seen – forms both living or dead – and in its ability to emulate the universe with its marvellous interplay of relationships.” [70]

Painting is therefore pure image, to some

extent according to the logic of art for

art: “That a real work of art seeks only to render flesh as flesh, light as

light, is much too simple to be immediately understood. A perfectly painted

human body in repose, with the light gliding over it, in whatever way, and

which is only intended to express calm, no play od emotions of any kind, is in

itself a picture, a work of art. For the artist the ‘idea’ is to develop forms

appropriate to the position of the body, its relationship to the space, its colour

combinations, and it is of no consequence at all to him whether this is

Endymion or Peter. The idea is enough for the artist, and it is enough! But our taste nowadays first

demands to know for sure if this might not be Endymion.” [75] Klinger sees with

concern the attempt of modern painting to deviate from tasks exclusively

related to the composition of artistic forms, and instead of devoting

themselves to the promotion of messages, to the narrative of events: “Modern

art is permeated by this novelistic urge, which seems completely to have

swamped the natural form in repose. It takes an immense effort on the part of

the artist to work his way out of the floods and to arrive at a simple,

artistic view and, instead of seeking art in adventure, to seek it instead in

Man and in Nature.” [76]

Therefore, painting is absolute joy. “If we

consider the language of painting, it seems to us the most perfect expression

of the joy of life. It loves beauty for its own sake and strives for beauty

even in the ugliness of the mundane of the depths of tragedy. And when it

touches us, it does so by all that is charming, by the harmony of forms and

colours, even though there may be contrast. Painting is the glorification, the

triumph of the world. And it has to be so.” [77]

The purpose of drawing

Beauty and joy cannot exhaust the creative

experience of the artist. "To feel what he sees and to pass on what he

feels is the crux of the artist’s life. But is this to say that the powerful

impressions (…) with which the dark side of life inundates him, should be

silenced, although he, too, seeks help in the face of these? The terrible

contrast between the beauty that he seeks, sees, feels and the awfulness of

existence – which often comes screaming towards him – has to give rise to

pictures, just like those that come to the poet and the musician from their own

experience of life. If these pictures are not to be lost, there must be another

art to complement painting and sculpture, an art without the calm presence of a

plastic form that would come between these pictures and the beholder as it does

in painting and sculpture. This art is drawing” [78].

-

It gives the imagination free

reign to add colour to the representation;

-

It can handle forms that are

not part of the main point – even the main point itself – with such freedom

that again the imagination is called into play;

-

It can isolate the subject of

the representation such that the imagination must create the space around it;

-

And it can utilize these means

either singly or together, without the resulting drawing suffering in the

slightest in terms of its artistic value or perfection.” [81]

“The stylus has a much narrower light-dark

range than the palette. The latter has greater succulence and power in its dark

tones and more energy in its light tones, which are heightened yet further by

the contrasting effects of warm and cold tones and by colour combinations. But

although the palette has the advantage of intensity and colour, the stylus makes up for

this with its unlimited capacity to represent light and shade. It can portray

direct light and direct darkness – sun, nighttime – whereas painting can only

portray reflections and contrasting shadows. The ring, for instance, that

stands for the sun in a drawing is quite sufficient to convey to us its nature

and effect, just as nightmare, too, can be expressed in a few allusions, with a

minimum of contours and tonal indications. This arises from the poetic nature

of drawing mentioned earlier, for drawing does not so much depict the

appearance of things, in the interplay of things, in the interplay of their

visible forms and the ensuing relationship and effects, as convey to the

beholder the ideas that are intrinsic to them” [82]

Drawing is the world of poetic license,

that it is constitutive of poetry. “And the visible corporeal world can be

treated with such poetic license by virtue of the freedom e have already

mentioned, which allow motifs to be portrayed as phenomena rather than bodies.”

[85]

But Klinger goes beyond the poetic, to

discuss the horrible (Unschönes):

“Given such ideas and licence, drawing also has a different relationship with

the unsightly and the abhorrent than do other arts. The visual arts [bildende Künste] are predicated on

defeated unsightliness; the spoken arts [die

redenden Künste] have yet to defeat unsightliness.” [86]

Drawing provides artists with the

greatest freedom: “The wealth of the raw material that goes into drawings – the

same material on which religions are based, for which nations annihilate each

other, which we so gladly ignore, and which the human spirit therefore seeks to

conceal using anything at its disposal from the naives of simple-mindedness to

the most grotesque outrageousness, a material kept in constant ferment by

egoism and self-sacrifice – such wealth suggests that ideas and images shower

upon the artist in abundance. (…) The most powerful emotions can be compressed

into the most confined of spaces, the most contradictory emotions come thick

and fast. (…) They may be of epic dimensions, they may take on a dramatic

intensity, they may regard us with dry irony; mere shadows, they even embrace

the monstrous without causing offence.” [87]

It remains still to identify the reasons

why drawing acquired the dignity of artistic genre only after the discovery of

the press: “Success does not match the effort involved. Moreover, in the epoch

that strove for splendour, drawings – unostentatious and barely accessible in

the hands of a few individuals – had little appeal for artists. The material

itself had little to do with the love of colour of those days. And in any case

there were rich opportunities for artists to give vent to their imaginations on

the walls of dwelling houses, churches, palaces. (…) The invention of printing

altered the situation. The possibility of producing multiple copies removed the

disparity between effort and success. The work no longer disappeared into a

library but, in its multiplicity, could expect the same chorus of appreciation

as any wall painting. The stylus – more powerful, richer in tone yet with all

the delicacy of hand-drawing – offered the individual as great an opportunity

to develop an independent mode of expression as any painting could do. Woodcuts

and engravings – and later on etchings and lithographs – opened up to the

artist’s initiative and invention a field that was infinitely varied, promising

and surprising.” [88]

Why the separation between painting and drawing is absolutely required

In Klinger’s thinking, the technical factor

is really central. To different techniques must correspond equivalently different

artistic purposes: “every material has its own spirit (Geist) and its own poetry which derive from its appearance and its

amenability, and which – in the hands of the artist – reinforce the character

of the composition and are themselves irreplaceable.” [89] And again: “The direction of our

discussion could be summed up as follows: a motif, which can be rendered as a

drawing in a wholly artistic manner can, for aesthetic reasons, be impossible

to render as a painting – insofar as the painting is to be judged as a picture." [90]

“All masters of drawing develop in their

works a conspicuous streak of irony, satire and caricature. They delight in

pointing out weaknesses – anything sharp, harsh or bad. The basic tenor of

almost all their work is: The world should not be like this! So they criticise

with their stylus. The difference between the painter and the graphic artist

could not be described more pointedly. The former creates forms, expression and

colour in a purely objective manner. He does not really criticise; he prefers

to beautify. This is also a critique, but not a negative one, and it tells us,

‘This is how things should be!’ or ‘This is how things are!’ For in his mind’s

eye he sees a spiritual, all but physically attainable primal image of beauty

that he recognises. The graphic artist, in contrast, is confronted by the

eternally unfilled gap between desire and ability, between yearning and

achievement, and he has no choice but to come to term, on a personal level,

with a world of irreconcilable forces.” [93]

End of Part Two

Go to Part Three

NOTES

[42] Max

Klinger. Wege zur Neubewertung. Schriften

des Freundeskreises Max Klinger e.V. Band 1 (Paths towards a revaluation. Writings of the circle of the association of the friends of Max

Klinger. Tome 1), edited by Pavla Langer, Zita Á. Pataki and Thomas Pöpper,

Leipzig, Zöllner, Plöttner Verlag, 2008

[43] Avenarius, Ferdinand, Max Klinger als Poet. Mit

einem Brief Klingers Max und einem Beitrag von Hans W. Singer (Max Klinger as a poet. With a letter by Max Klinger and a contribution by Hans W. Singer).

Published by the magazine Kunstwart, Edition of war, Munich, Callwey, 1918

[44] Klinger, Max - Malerei

und Zeichnung: Tagebuchaufzeichnungen und Briefe. (Painting

and Drawing, Journal and Letters), edited by Annaliese Hübscher, Leipzig,

Philipp Reclam jun., 1985

[45] Billeter, Felix - “Max Klingers Schrift 'Malerei und Zeichnung'. Ein Blick auf ihre

Entstehungsgeschichte“ (The writing by Max Klinger ‚Painting and Drawing’,

A view on the history of its genesis), in Festschrift für Christian Lenz. Von

Duccio bis Beckmann, Verlag Blick in die Welt, 1998, pp. 65-83.

[46] Juntunen, Evelina – Genuin grafisches Schaffen – Malerei und Zeichnung (1891) und Klingers Zelt (A genuine graphical

creation, Painting and Drawing (1891)

and the Tent by Max Klinger) n “Wege zur Neubewertung“ 2008 (quoted)

[47] Morton, Marsha – “Malerei und Zeichnung”: The

History and Context of Max Klinger’s Guide to the Arts, in: Zeitschrift fü

Kunstgeschichte, Year 85, Vol. IV (1995), pp. 542-569.

See also: http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/1482810?sid=21105552302593&uid=3737864&uid=2478518977&uid=2134&uid=3&uid=2&uid=60&uid=2478518987&uid=70

[48] Pendleton Streicher, Elizabeth -

Max Klinger's Malerei und Zeichnung: The Critical Reception of the Prints and

Their Text, in: Studies in the History of Art, Vol. 53, Symposium Papers XXXI:

Imagining Modern German Culture: 1889–1910 (1996), pp. 228-249. See: http://www.jstor.org/discover/10.2307/42622157?sid=21105582739343&uid=3737864&uid=70&uid=2134&uid=4&uid=2

[49] Ms Pendleton Streicher wrote

instead that the text style, in her opinion, is too informal, typical of conversations,

almost absently written and somewhat repetitive. She attributed the reason to

the fact that Klinger had begun to fill the text starting from the pages of the

diary of 1883 and the letters of the following years. She adds "In its aphoristic

style, Malerei und Zeichnung is rooted

in a long tradition of writing in German aesthetics and philosophy, which culminated

in his own day in the publications of Friedrich Nietzsche. Nonetheless, Malerei und Zeichnung is simply and

symmetrically organized. "Pendleton Streicher, Elizabeth- Max Klinger's

Malerei und Zeichnung: (quoted), p. 233

[50] Klinger, Max – Gedanken und Bilder aus der Werkstatt des

werdenden Meisters (Thoughts and pictures from the workshop of the master

in his education years), edited by H Heyne, Leipzig, Koehler & Amelang,

1925, p. 115.

[51] Klinger, Max – Gedanken

und Bilder … (quoted), pp.16-20.

[52] Marsha Morton also cites a letter

of February 23, 1883, therefore before the stay in Paris. See Morton, Marsha -

"Malerei und Zeichnung"

(quoted), p. 543.

.

[53] Dantini Michele – Un paragone tra le arti (A comparison

between arts), in: Klinger, Max - Painting and drawing, edited by Michele

Dantini with an essay by Giorgio de Chirico, Milan, Nike, 1988, p. 129. The

quote is on page 53.

[54] For a description of the Klinger

fund and the files on Painting and

Drawing maintained in the archive of Lipsia, see

[55] The correspondence contains a

three-page letter to Albers (for whose villa in Berlin Klinger composed an

important cycle of frescoes) devoted entirely to the subject of the

relationship between painting and drawing, dated Paris, February 24, 1885. See: Briefe

von Max Klinger aus den Jahren 1874 bis 1919 (quoted), pages 64-66. In the diary of Klinger there are references to "painting and

drawing," March 22, 1885. See: Klinger, Max - Gedanken und Bilder ... (quoted), p. 38.

[56] Klinger, Max – Gedanken

und Bilder … (quoted), pp.103-104.

[57] Pastor, Willy –Max Klinger, with a drawing in the cover

page by the author, Berlin, Amsler & Ruthardt, 1918 The chapter on the stay

in Rome is from page 120 to page 150.

[58] Morton, Marsha – “Malerei und Zeichnung”(quoted)

[59] See: Briefe

von Max Klinger aus den Jahren 1874 bis 1919 (quoted), page 64-66.

[60] Here is what Klinger writes in

this regard, during the visit to the Triennial exhibition of Paris in 1883:

"Here I would like to refer to an almost disappeared technique, which

unfortunately is no longer applied in Germany. It is painting-engraving. It is

different, here [note of the editor: in Paris] as well as in London. Each show

brings rich contributions of this branch of art. With the indifference of our artists,

publishers and of the public (two out of three do not have any idea), a lot

should happen before etching may have the same fortune with us. See French,

British, Belgian publications which are not intended for mass consumption. If

there are illustrations in those publications (it happens to be the case in a

publication every two), they are etchings.” Klinger, Max - Gedanken und Bilder

... (quoted), p. 29

[61] All English translations are from

Fiona Elliot and Christopher Croft. Klinger, Max - Painting and drawing,

Birmingham, Ikon, 2005.

[62] Klinger, Max - Painting and

drawing … (quoted) (p. 27)

[63] Klinger, Max - Painting and

drawing … (quoted) (p. 27)

[64] See the essay of Max Deri on

Naturalism, idealism and Expressionism, published in Leipzig in 1920 (https://archive.org/details/naturalismusidea00deri)

[65] For an English version, see: The

Blaue Reiter Almanac , by Klaus Lankheit, Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, MFA

Publications, 2005

[66] Morton, Marsha – “Malerei und Zeichnung”(quoted),

p. 556

[67] Morton, Marsha – “Malerei und Zeichnung”(quoted),

p. 556

[68] Klinger, Max - Painting and

drawing … (quoted) (p.13)

[69] Klinger, Max - Painting and

drawing … (quoted) (p.13)

[70] Klinger, Max - Painting and

drawing … (quoted) (p.13)

[71] Klinger, Max - Painting and

drawing … (quoted) (p.14

[72] Klinger, Max - Painting and

drawing … (quoted) (p.17)

[73] Klinger, Max - Painting and

drawing … (quoted) (p.17)

[74] Klinger, Max - Painting and

drawing … (quoted) (p.17)

[75] Klinger, Max - Painting and

drawing … (quoted) (p.18)

[76] Klinger, Max - Painting and

drawing … (quoted) (pp 18-19)

[77] Klinger, Max - Painting and

drawing … (quoted) (p.19)

[78] Klinger, Max - Painting and

drawing … (quoted) (p.19)

[79] Klinger, Max – Painting and drawing

… (quoted) (p. 23)

[80] Klinger, Max - Painting and

drawing … (quoted) (p. 21)

[81] Klinger, Max - Painting and

drawing … (quoted) (pp. 20-21)

[82] Klinger, Max - Painting and

drawing … (quoted) (p. 24)

[83] Klinger, Max - Painting and

drawing … (quoted) (p. 11)

[84] Klinger, Max - Painting and

drawing … (quoted) (p. 21)

[85] Klinger, Max - Painting and

drawing … (quoted) (p. 21)

[86] Klinger, Max - Painting and

drawing … (quoted) (p. 21)

[87] Klinger, Max - Painting and

drawing … (quoted) (p. 22)

[88] Klinger, Max - Painting and

drawing … (quoted) (pp. 30-31)

[89] Klinger, Max - Painting and

drawing … (quoted) (p. 12)

[90] Klinger, Max - Painting and

drawing … (quoted) (p. 13)

[91] Klinger, Max - Painting and drawing …

(quoted) (p. 23)

[92] Klinger, Max - Painting and

drawing … (quoted) (pp. 28-29)

[93] Klinger, Max - Painting and

drawing … (quoted) (p. 29)

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento