CLICK HERE FOR ITALIAN VERSION

German Artists' Writings in the XX Century - 3

Lovis Corinth

Autobiographic Writings. Part Two

(Review by Francesco Mazzaferro)

[Original Version: October 2014 - New Version: April 2019]

GO BACK TO PART ONE

The Autobiography (1916-1926)

She was the one who

drafted the Autobiography in 1925 –

bringing together the separate parts she found in the desk of the husband - and

organized their publication in 1926. She became part of the jury of the Berlin

Secession and there she exhibited his paintings. She exhibited at the Venice

Biennale in 1926. In 1927 she opened her own school of painting. Jewish, she had

the intelligence to leave the country with her two children as soon as the risk

of a Nazi victory became apparent. It was not always so: many others were sure

nothing would happen to them. The wife of Max Liebermann and Carl Hofer's first

wife died in a concentration camp, because remained blocked in Germany, where

emigration became impossible with the war. Charlotte moved to France and from

there to Italy in 1932, where she lived first in Alassio and then in Florence,

for a total of a five year stay in Italy. The Italian Riviera was for her a

kind of shelter: Bordighera was the place where she had helped Lovis to recover

from a stroke in 1911. In Florence she was reached in 1935 by his sister Alice,

a famous writer in those days, together with the family. [73] Shortly before

the racial laws, Charlotte left Italy and moved with her children first to

Switzerland and then in 1939 to the United States, where she continued the art

carrier. She died in 1967.

In 1937 she completed a touching collection of imaginary letters to her husband, My Life with Lovis Corinth (Mein Leben mit Lovis Corinth), but could not publish it: Corinth had been included in the list of Degenerate Art, and she was Jewish. It will be released in 1947, after the end of the war. In 1958 she published a second book, titled Lovis, and the same year the catalogue raisonné of the works of her husband. She lived the second half of her live in the US, but her archive is stored at the Academy of Fine Arts of Berlin [74].

NOTES

[Original Version: October 2014 - New Version: April 2019]

GO BACK TO PART ONE

|

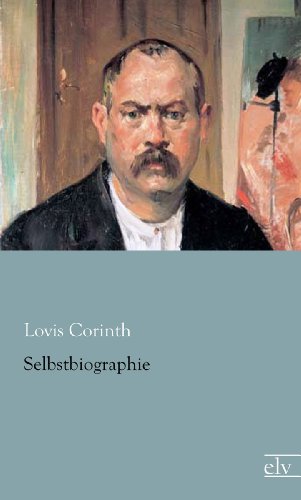

| Fig. 4) The first edition of Lovis Corinth's Autobiography, published posthumous by S. Hirzel in Lipsia (1926) |

The Autobiography (1916-1926)

Let us now

consider the Autobiography. It is

absolutely clear that it has a completely different nature from the

auto-biographical novel From my life

in the Legends. The Autobiography is obviously rooted

in reality. If the Legends reflect in

fact the techniques of symbolism, many pages of the Autobiography are marked by the techniques of naturalism.

We know from the

evidence collected by the son Thomas that the painter had already produced some

drafts of the Autobiography in 1892,

the year of creation of the Munich Secession. Then, as it has been said, he

wrote the Legends in 1908. He

returned to the project of an Autobiography

in 1916.

The literary

ambition of Corinth was certainly very high. And yet, this text is not without

obvious problems. The Autobiography

is the sum of three parts, each dissimilar in style and intention from each

other, and made at different times. The first part, dated 1916, covers the

years of his youth. The second part of the Autobiography,

dated 1917, covers the years of his progressive artistic maturation until 1900,

and - in fact – it is very disappointing, because it is lost in the meandering

of friendships and personal enmities, instead of centring on the question of

art. There is then a gap of fifteen years, between 1900 and the First World

War: a single page recalls the cerebral stroke in 1911 [24] and ten pages are

devoted to the disputes between the painters of those years. [25] In practice,

these fundamental years between 1900 and 1914 are not covered, except for very

broad hints. The third part of the Autobiography,

dated 1925, narrates the ten years after the First World War, until a few months

before the author’s death in 1925. In fact, the third part is an intimate and desperate diary and no longer has the tone of story-telling.

More than a

collage between different parts, the Autobiography

is a mess, a mess which the wife has, however, decided to publish in this form

in 1926, out of respect for her husband. The style of writing is at times very

choppy. "For me it was difficult to reach the conclusion of the

description of my life. You can never get to a definition on your character. I

have the biggest dissatisfaction with my writing style. Back in school, I

received mixed reviews as writers of essays in German. As an ideal type of

writing, I would give the highest rating to the Confessions of Rousseau. Then, I admire the style of Lessing, and I

would try to write along the same line. But both are impossible to me, and I

will never improve. The main thing for me is to capture my character in a

concise form. I want to show me as an artist". [26] The Memoirs of the painter Anselm Feuerbach are the other literary model, as "they

are the only ones to have great value." [27].

It was not,

however, a publishing success: remarkably, Charlotte Berend-Corinth – the wife

and editor – does not offer any description of the public and commercial

success in her My Life with Lovis Corinth

of 1947. Michael Zimmermann reports a very positive assessment by the art

critic Julius Meier-Graefe. [28] However, after the first edition, the Autobiography was never published again

until 1993, the date of the volume that I have consulted, published by Kiepenheuer

Verlag in Leipzig. The new pocket-sized publication by the publisher Holzinger,

printed in Leipzig in 2013, has made again of the Autobiography a readily available volume. There is no translation

into another language.

The three parts of the Autobiography

The first third

of the text (80 pages out of 226) is on the years of childhood and adolescence.

A separate and more extensive edition, with the title "Meine frühen Jahre" [29] or "My early years", was published by his wife in 1954.

Apparently, as she writes in the introduction, she discovered of the existence

of a wider and different edition of the memoirs on his youth, justifying the

new edition in 1954, while rearranging the papers of her husband.

This first part

of the Autobiography, which was

written in 1916, has literary ambitions of a naturalistic type, as already

mentioned. In some respects, while reading those pages, we seem to be in a

picture by Leibl or Courbet, painters who were very close to the heart of

Corinth. There is no doubt that the intention is to describe the environment

and modest provincial family in East Prussia, including Könisberg and Frankfurt

am Oder. Already the transition between the rural village of Tapiau where he

was born (now in Russia: Gwardejsk) and Könisberg, (today the Russian

Kaliningrad), where he first lived as a young man and then studied, marks the

conflict between two worlds: the young Corinth barely speaks German and when

opens his mouth in the schoolroom on the first day, he even does not know

how to properly pronounce his last name, sparking a big laugh in his class [30],

perhaps the most beautiful and sober page of the story of life. Among the greatest

satisfaction for Corinth, was the opportunity to return to Tapiau many years

later, by then being a famous and revered painter, like during the war in 1916 and

in the last months of life in 1925. [31]

What is

striking, however, is that in the final pages of his autobiography - those

written closer to the death - the painter reconsiders some of the themes of his

childhood, with a tone of deep bitterness, revealing that he had always suffered

from depression since then, he had a mother who was cold and devoid of empathy,

was hated by her aunt - where he lived in Könisberg - and had suffered wrongs

and hostility from the half-sister. Only the father seems to remain a reference

point for the young Corinth and a remembrance full of nostalgia for the old

Corinth. His wife Charlotte wrote in her "My Life with Lovis Corinth" of the portrait of his father,

which Corinth had hanged in the apartment, of the desk used by Corinth, which

belonged to his father, and the fact that the artist was thinking at least

every two days to the father [32].

The second part

of the memoirs is completed in 1917, when Corinth approached sixty years. It

speaks of the academic education in Könisberg and Thuringia (and of his

drinking excesses, which would prejudice his health forever). Corinth owes to

his favourite professor (Otto Günther, a painter of the German realist school

of the middle nineteenth century) the advice to go to Munich, one of the

centres of innovation of European painting, where he arrived in the 1880s and

studied with Ludwig von Löfftz, a landscape painter and especially an excellent

teacher of drawing. He will always be fond of Günther and will register with

bitterness his progressive marginalization and ultimately his premature death

in solitude.

As mentioned above,

this section of the work includes the writing entitled "Intrigues and observations", which

begins with the observation that "the stronger the individuality of an

artist, the more he is exposed by the public to misunderstandings." It is

the part of the autobiography which focuses the most on the intertwining of

aesthetic issues and the lives of artists, and reaches, pessimistically, the

conclusion that intrigues are always present in an artistic career. The whole

exhibition is tinged with disillusionment: for example, Corinth writes that he

went on a study trip to Belgium in 1884 and not to Paris, for fear of

retaliation after the Franco-Prussian War of 1871. In reality, he moved to

Antwerp also for the sake of Flemish art. Then - disappointed by his teachers

and probably very lonely ("A true Eastern Prussian cannot mingle with

strangers" [33]) - decided to move to Paris, where he lives in total for

four years, until 1887, although also there without great enthusiasm. It is no

coincidence that this section of the autobiography is written during the First

World War. After returning from France, began for him a confused phase, in

which he first returned to Berlin, then to Munich and moved several times

between the two cities, in search of other artists, friends and wealthy people

ready to buy his paintings. Munich has more tradition as artistic centre,

Berlin as a metropolis is more dynamic. Finally, he chose Munich in 1891 and

entered the local Secession (the first one in Germany), getting acquainted with

the symbolism of Franz von Stück. It is not long, and Corinth dissociates himself

from the Secession of Munich and creates – together with nine other colleagues

(the most famous of whom was Max Slevogt) - a 'free association' (Freie Vereinigung), a rival to the Secession,

which is immediately isolated and marginalized. Repeating what I have already

noted in a previous article on Max Pechstein: in those years, groups of artists

were born and melted continuously, as it happens nowadays with rock bands.

In Munich

Corinth knows the first commercial successes, like with the "Deposition" in a symbolist /

secessionist style; he failed however to carve out a specific role and a

sufficient space for himself. When his "Salome with the head of John" is rejected by the jury of the

Secession, he realises that the time has come for a change of air. Following an

invitation of Walter Leistikow and Max Liebermann, he moved to Berlin, entering

the local Secession. In Munich he left only two or three friends: Eckmann,

Strathmann, Theodor Heine. He felt the need to portrait them (Eckmann) or - as

already mentioned - to write critical reviews on them (Strathmann, Heine). As already said, after the suicide of Leistikow (1865-1908), he

decided to write a biography.

In Berlin he

finds with "Perseus and Andromeda" the great success that he has been

waiting for since time. Soon after, he decided to create a school for female painters,

triggering the hilarity of many colleagues. In addition to a lot of

satisfaction, the school will bring him Charlotte Berend as a wife (his first

student) in a happy and close-knit pair. Only Leistikow, perhaps the only truly

painter friend in Berlin, supports him.

Although

included in the Berlin circle of the Cassirers (we already mentioned his publications

for Bruno and Paul) and connected to Liebermann and Slevogt as impressionist

since the time of Munich, Corinth was a man capable of a few enduring

friendships, and will always find a way to arguing with all of them. Of Paul

Cassirer he hates the centralist attitude, and the intriguing character; they

will end up going to court the one against the other. With Liebermann and

Slevogt he disputes in 1911, when tensions begin to occur among all painters of

the Secession. Moreover, the same Liebermann and Cassirer turn each other their

backs. A war of all against all. His wife Charlotte Berend describes in "My life with Lovis Corinth" the

long quarrel of her husband with Max Liebermann, which also ruined her

personal relationships to Max. The rupture occurred when Corinth took the chair

of the Secession in 1911; Liebermann and Corinth only make peace again in 1925, the last year of life, in front of the President of the Republic Friedrich Ebert. Despite this, the pages of Corinth on

Liebermann in his Autobiography

remain very negative. The wife sees Liebermann for the first time after twelve

years, in 1926, at an exhibition on the graphics of Corinth, who was already dead

[34]. Such a long break was a collateral damage of the attack of Nolde against

Liebermann [35] and the creation - even against Corinth – of the New Secession,

the one with the expressionists: the group of the Brücke (Bridge), Nolde, and many others. Liebermann accused Corinth of not

having defended him to the end from the expressionists and to have used the

opportunity to get elected president of the Secession, at his place. Presidency

that Corinth must leave immediately, after the stroke of 1911. In 1915, Corinth

takes the presidency of the Secession, again. But now he is the leader of a small group

of very conservative artists (that conservative secession will be called “The

Trunk Secession”, i.e. Rumpf-Sezession).

After he had quarrelled with Liebermann and Cassirer, his point of reference in

Berlin becomes Fritz Gurlitt; it is with him that he will publish his writings

(Schriften) in 1920.

The following

sections (from section four to section eight) are the third and final part of

his Autobiography, dated 8th

May 1925, shortly before his death. Corinth died soon after, on 17th

July, because of a pneumonia during a trip to Holland, made to admire the work

of Rembrandt and Frans Hals: together with Rubens, they were the painters who

had always loved most.

This final part

is characterized by a discontinuous narrative, sometimes in the form of a

continuous story-telling and sometimes in the form of a diary, in which the

events are presented day by day. The disconsolate considerations of the artist prevail,

commenting on a number of serious historical and personal traumas, and are partially balanced - in the last pages - by the joys of family life. The first

trauma is the stroke that hits him in 1911, at the time of maximum artistic

fame in Germany (at that time, as just recalled, he presided over the Berlin

Secession); the second trauma is Germany's defeat in World War I, considered

also as the sign of the historical difficulty for Germany of creating the

foundation for a strong culture of national orientation; the third trauma is

the economic, political and social crisis of the Weimar Republic.

This does not

mean, however, that there is no hope. There are five solutions: a renewed

German art, based on full spiritual freedom; eroticism, as a source of energy;

the family; the rest and the painting activity on the Bavarian lake Walchensee;

and finally (as a result of all the above mentioned, both positive and negative

aspects), the conquest of a renewed pictorial style that places Corinth in the

field of modernity.

Some topics of the Autobiography

a) The diseases (ictus, alcohol and depression)

As already

mentioned, in 1911 Corinth is hit by a stroke. The only direct reference to

that event in the Autobiography a

"Fragment" [36]. It was a terrible blow, which put a strain on his

ability in the midst of a phase of intense activity, if you think - for example

- that Corinth had written a lot on arts in previous years, publishing a volume

each year (the “Legends”, the manual

"Learning the painting,"

the "Life of Leistikow").

With self-restraint, Corinth does not say anything specific on what happened in

that moment, but he tells us that his whole life suddenly flows in front of

him, forcing a rethink. A year later, in 1912, he painted the blinded Samson, a symbolic picture of

the disease.

|

Fig. 5) - The second edition of the Autobiography published by Kiepenheuer in Lipsia in 1993 |

It is then in

the final pages of the Autobiography

that one would discover that Corinth has always lived with diseases, both from

the physical and from that nervous point of view. He speaks of it, after having

reached the pinnacle of success, with a large retrospective exhibition

organized by Ludwig Justi at the National Gallery in Berlin on the occasion of

the sixty-five birthday, in 1923, "Diseases, a paralysis of the left side,

a monstrous right hand tremor strengthened by the efforts by the needle

[editor's note: for engraving] and caused by previous excesses with alcohol,

prevent me from doing any calligraphic craftsmanship. A constant effort to

achieve my goal - I've never reached the degree hoped - has exacerbated my

life, and every job has ended with the depression of having to go on with this life."[37]

"Actually I was - I can say, from my childhood - tormented by the most

severe melancholy. There is no day in which I have not thought it would be best

to separate myself from this life. Only one thing made the difference: I have

not ever done it. I was afraid of owing to repent it. For this reason I avoided

the possession of any weapon, revolver, or dagger. Nor did I ever owned a

shaving razor, I never wanted to leave me take my hand, make a rush that was

not right." [38]. " Yet, I

have been unhappy all my life. Earlier on, this underground war against me by

my half-sister, a continuous fight, why she had not received any formal

education, a secret persecution of my life. This situation has been with me since

childhood until today. (...) With my character I have not loved anybody and I

seemed (...) rather disgusting and gross to all. To this, an envious spirit

added up showing repulsion towards each serene appearance and every higher capacity. A burning

ambition has always tortured me. Not a day passes when I would not damn my life

and I would like to finish it." [39]

"Berlin, 13th August 1923. Today I suffer again from a severe form of

depression. For days, I have tried to paint a sketch of the "Prodigal

Son." I want to try to describe this state from the truth. I realised that

my painting is really a pure crap. Life has no meaning, there is no

perspective, there is a dark curtain, to which I'm adding the anger I have towards

me and my work. I forgot my abilities and I would like to trumpet to the world:

what do you find in me, I am a poor unfortunate! Do not you realise that I am

nothing - not an artist - nothing – I am pathologically depressed - all around

me there is no ray of sunshine; my whole life was useless." [40]. And the last year, in 1925, after

speaking with enthusiasm of his "Trojan

horse", he writes:" I have exalted my works in a particular way,

just because in no other period of my life I have been so much visited by moral

depressions as in this time. I would cry. A dump of each painting captures me.

Why do I continue to work? Everything is garbage. This horrible inertia in

continuing to work makes me sick. I am 67 years old, this summer I will get

close to 68. What needs to flourish again?" [41] That summer, he will die.

The report of

the wife Charlotte on her husband's illness is really dramatic: a severe

depression attacks him every two days. She has learned how to react to them,

being in fact his therapist. [42]

b) The war

It is only by

reading in parallel Max Sauerlandt’s lessons in Berlin on “Art in the last thirty years” [43] and the article by Maurice Denis

on "What will be French painting

after the war" [44] that one can realise how the artists in Germany

and France - in spite of the similarity of the stylistic guidelines - were part

of a head-on collision between two cultures which considered themselves as a

priori enemies, a collision which started around 1880-1900 and of which the military

conflict of the First World War represented a kind of tragic extension. In

short: if the war happened, it is also because the two cultures hated each

other. It was not only the responsibility of the military, politicians and

industrialists. Even painters wanted war. There are really paradoxical

elements: in the veritable "civil war" among the conservative and avant-garde Berlin painters in

the early decades of the century, Corinth was long seen as the symbol of impressionism (a French orientation of

style) against expressionism (a

German orientation of style). Yet, this was not at all his personal

perspective. He lived four years in Paris, but there he did not integrate at

all, and often spoke of the harassment suffered at the Académie Julian in his autobiography. He paid the price of being

German (and therefore be responsible for the French defeat in Sedan and the

loss of Alsace and Lorraine). For once, it is not the fault of his bad charachter: also another important painter of those years, Max Klinger (1857-1920) reports of the same nationalistic hostility during his 4-years stay in Paris (1883-1887). Once Corinth is back in Germany, to him his main task was to

prove that the German art was at least equal, if not superior, in terms of

talents to the French one (he repeats it several times). And then, if the

stylistic results between Corinth and Nolde are very diverse, his anti-French

polemical arguments are very similar to those of Nolde, the patriarch of the

anti-classical and anti- French accents in artistic literature of that era. Indeed,

often the chauvinistic tones of Corinth are more pronounced than those of

Nolde.

It is taking

into account these beliefs that you have to think about the radical desperation

of Corinth for the defeat, which - in the end – was for him especially the

finding, once again, of the inferiority of his Prussia to France, despite of

any attempt to prove the contrary. "We have lived through the upheaval of

the German Empire against the whole of Europe, and those who were able to

experience it, saw an event that went far beyond the heroic representations of

the ancient world. The confidence in the Kaiser, in the command of the

military, and finally the absolute confidence of victory were so steadfast

(...) that those who were chosen for this holy war were regarded by all as the

happiest of the mortals. The parades of troops touched even the hardest of

hearts. The troops, covered with flowers and all concentrated in singing,

approached the station; children ran to their side, accompanying fathers and

brothers, and proudly wore their helmet or brought their weapon. We often saw

the father and the son - both soldiers - hugging, maybe paying farewell and

then joining their respective platoons on the march." [45]

Eventually, the

war is lost. And yet, writes Corinth, "we can ask if the winner comes out

of this bloody battle as a true winner. (...) If the winner imposed himself in

a horrific blaze of glory with a crown dripping with blood, advancing with a

purple smile on a devastated ground among the corpses, certainly he will not

take care, such as restraint and good manners instead would impose, of the mean

demand if it behaved in a barbaric or criminal manner in the conquered lands.

It will cut the Gordian knot, and dictate its laws to the world." [46]

c) The crisis

The war is over,

and the wind of the revolution is blowing. "Shame!" Writes Corinth,

and he blames the social-democratic click. [47]

"The future is dark, terrible. (...) I feel Prussian and I think Prussia is

the only state which can save us ", under the guidance of the Kaiser and

the military. [48] "The revolution

broke out" - writes on 10th November 1918 and repeated: "I

feel a Prussian and an Empire German (Kaiserlicher

Deutscher)." [49] A week later

he notes: "The Social Democrats have the big voice. They took the power

that the military had before" [50], and on 7th December 7 1918

he adds: "The power of the military has been destroyed forever." [51]

A succession of notes of despair continues: "The state bankruptcy is

around the corner"[52]. On 10th January 1923 he notes: "The dollar

has reached 10,000 marks. Inflation takes over, people do not know what will

ever happen. (...) The newspapers speak of 'decadence of Europe'. If only it were

really so: I see, however, only a collapse, the 'end of Germany'. No avenger

has arrived: no Moses or no Bismarck" [53] And it is of 31 August 1923: "The

final act of the collapse is approaching its conclusion: Germany goes to pieces

and is divided into separate parts. I hope my prediction is wrong, but ...

Goodbye! " [54]

The profound

crisis has however also paradoxical effects. The overwhelming inflation

destroys the value of money, and therefore creates a commercial interest in the

high bourgeoisie for safe haven assets such as works of art. This creates on

the one hand incentives for speculation, but also allows the painter to reach

economic success, at least until the economic measures of adjustment in 1923

(which put an end to inflation) reduces the liquidity in circulation. However,

his paintings on Walchensee (the resting place of summer in Bavaria) are all

the rage. "I have never sold so many paintings as after the collapse. I

had them literally pulled out from the atelier, and there had never been such a

proliferation of exhibitions throughout Germany. That our paintings were

considered a safe investment instead of money unstable, it is absolutely

certain." [55] And then he adds: "Just

at the time of the end of the war, I reached a huge success thanks to the

motives of the Walchensee, both in financial and ideal terms. Everybody in

Berlin wanted to have a picture of that corner of the Bavarian mountains, and

so it happened that, in addition to still lives, I specialized in this

beautiful corner of the Walchensee." [56]

d) A renewed German Art

The war is lost,

the country is in crisis, but Corinth believes this is an opportunity to

reconstruct the German art: "The country is destroyed: at work!" [57] The task is to reconstruct the German

art independently from that of the French art, and Corinth, as President of the

Berlin Secession (after 1915, a conservative Secession, as already mentioned),

assume this role. "I have never been a coat hanger or a flatterer. I've

always enjoyed French art, but I never imitated it. I have spoken, I have

written and I am committed to German art, and I was convinced even before the

World War that the German art would have exceeded the rank of excellence of the

French. Now, we need to have confidence in ourselves and to enjoy independence.

This is not megalomania, because I lived for four years in Paris and I have not

found among my fellow students anyone who had a talent that could not be

compared with the Germans." [58] This

same concept is repeated two more times, a sign (we have already seen, it is

the conclusion of From my Life in the

Legends) that those French years really

branded Corinth, creating in him a sense of unease. "In the autumn of 1884

I went to Paris. The spirit that greeted me was certainly more impressive than

in Germany. I studied in a famous school. The French who I met there seemed to

me not at all equipped. Traditional views. I was there for three years. I never

found a talent. Among the Germans, in particular at the Academy of Munich,

there was a lot more momentum. I admire the French painting from Watteau to

Monet, otherwise there is nothing that can be said to be exceptional." [59] So, no love for any of the

post-impressionists. "My conscious motivation - writes in 1923, the year

of a retrospective exhibition of great success - was to bring German art up to

the highest level. I saw what the French artists could do since some time, we

could do much more. I spoke in front of our youth, I can say with

success."[60]

e) Eroticism

Just look at the

paintings of Corinth to realise how eroticism has played a role throughout all

phases of his life.

"It remains to explain - says the artist - what nowadays painters think on eroticism and in particular what I think on it. The public believes that this direction of art is indecent and can be seen only in isolated places. (...) I think in a different way. The soul life of people becomes much more impetuous under the pressure of sexual contact. As the music between human beings and the singing of birds is based solely on instinct sex, so painting is also a pure expression of the senses” [61]

f) The Walchensee

Another of the

pleasures of life - and perhaps the one for which Corinth is best known among

the general public - is the active rest at the Walchensee, the place where he at

the same time discovers the pleasure of outdoors painting (in a technical

sense, en plein air) and changes his

own style.

"For five

years we spent the summer on the Walchensee. I gave my wife a small plot of

land, and we have built a chalet. She has directed the work in a very astute way

and the chalet has therefore become her property, since I am really not

practical, and would have not been able to get away with the work. The chalet

offered a nice view of the lake, and soon I painted all the motives that would

become a joy for humanity." [62]

g) The family

The angel of

Corinth is his wife Charlotte Berend, twenty-three years younger than him, the

first of his painting students at the school for young female artists in

Berlin. He portrayed her in almost all situations. She was an independent

painter, and exhibited as Charlotte Berend even after marriage, in Germany and

later on in the United States.

"In

addition, a future that could not be more black. I could not bear it, if a spirit

had not comforted me, and had not supported and strengthened me in this misery.

The spirit that has sustained me in a human way, is the one of my wife and my

children. My wife, besides having a great talent and being my student before

marriage, is a woman of great intelligence and ability to anticipate and plan

events. It was really mostly her to support and to help me in all the difficult

situations of life today." [63]

h) The new style

What are the

aspects of modernity in the new style of Corinth? It has already been said.

These aspects can be discovered by a stunned admirer in front of his paintings

in recent years, much better than by the reader of the Autobiography.

Referring to the

last Corinth, Horst Uhr speaks of a new synthesis of content and form [64]. and

does not hesitate to refer to "a new expressionism" [65]. The new

sense of drama, the new use of color, the disappearance of well-defined

contours, the different way of portraying faces, a less attention to

sensuality, to the naked, and to decorative motifs are clear. His figures,

which previously dominated the narrative of the paintings, and indeed seemed to

want to get out of the canvas as a form of illusionism, are now immersed in the

landscape, with which they share shapes and colours. The narrative as a whole,

changes: if before the stories were perfectly done, now they seem sketchy; if

before the painter seemed to tell us live a mythological saga - almost like a

radio commentary - now is an irremediable nostalgic tale of the past that is

shown to us.

Really, of the

modernity of Corinth, the observer of his late paintings understands much more

than the reader: emotionally, Corinth was in fact a subject of the empire,

rejected the Republic and had a horror of any political renewal. A real

reactionary soul, with conservatism deeply entrenched in his heart, and ready

to justify the use of weapons to prevent that things will change. It must be

repeated again, therefore, in full clarity: the elements of modernity are to be

sought more in art and biography. And anyway, they are mainly related to the

execution of works than to the theory of art.

Please read with

which disdain Corinth speaks of the "modern" in the Autobiography. "In these modern

times, it was tango to be the winning ace and cubist painting and the naivety

of the African savages have beaten everything which was simple. In these times one

kicked the simple study of nature away. Our time was so boastful in its

indifference, that we no longer had the means to keep our senses awaken, for

they have fallen asleep by now." [66]

And this

corresponds to the decision to take over for the second time the presidency of

the Berlin Secession (the super conservative Rumpf-Sezession) after all the expressionist painters had already

gone away from it, and the same Cassirer and Liebermann have broken the bridges

with it. So, Corinth feels to be - in his heart - the last of the previous

generation. Moreover, in the calendars of the Secession exhibitions, Corinth

signs important statements against the avant-garde. He had already expressed

these views, first in an article in the aforementioned magazine Pan of 1910 (before the stroke) and then

in a lecture to German students of 1914. We are at war and Corinth knows to

speak to future soldiers, many of whom are going to die.

|

| Fig. 6) The third version of the Autobiography, published in 2012 by the Europäischer Literaturverlag in Bremen |

Here is what he

wrote in the Autobiography about that

lesson: "I preached in a speech to the German youth that we need to go the

way that leads to the holy German art, the way that our ancestors have shown

us. We want to show the world that today's German art is geared to reach the

top of the world. Enough of this simian imitation we made of Gallic-Slavic art

during our last period of painting. Today we want to cultivate that 'terrible

seriousness' of which I have spoken for years, when that false art was yet the

most popular. That 'terrible seriousness' is necessary for us to shake the yoke

of a foreign and dictate our German art. Dictate? The expression is too

arrogant. Rather we want to follow nature, each in their own way and according

to his own individuality, so that there cannot be anything missing to achieve,

with this holy earnestness, finally a German national art. You have to add yet

another element of which I spoke to the German youth. If you want to regenerate

German art, it is especially necessary to enjoy freedom of spirit. We want to

have freedom, because it alone can lead us to the summit we so badly

dream." [67] Modern art, he adds,

is the result of an epidemic that has originated from France, and has spread to

Spain and the Balkans, and intends to imitate the ingenuity of exotic and wild

men. Against this art - Corinth adds - we have already fought a war that looks

like the current one. [68] He talks to future soldiers in a war time, and the

enemy is the same. Modernity, therefore, is to follow the road that indicated

Leibl, Feuerbach and Victor Muller. And here is his assault against the German

Expressionists, which he calls "men without a country, that abuse of the

flag of youth progress." [69] They will focus on the colour, but theirs is

a pure hypocrisy: they focus on Leibl and forget Anselm Feuerbach. The conclusion:

there is a danger of losing everything that is typically German in our art. And

on 13th November he wrote "Art shall conquer freedom. It is

possible that the blood of the fallen has not been shed in vain. But the day of

reckoning is yet to come, I fear." [70]

On this, it was not mistaken: the worst would come after his death in 1925,

with the seizure of power of Nazism and the destruction of Europe.

A misunderstood painter?

If, therefore,

Corinth does not feel part of the avanguard, the reaction of the general public

with his art was still often characterized by the same attitude of disgust they

felt vis-à-vis most modern art. For instance, he tells us that his portrait of

President Friedrich Ebert was subject of such disputes to be withdrawn - at the

request of the President himself - from the halls of Kronkprinzenpalais, where the section of the National Gallery of

Modern Art was exposed. "As for my picture, I leave it in peace to the

judgment of posterity. In a few years, when the judgment will become more

neutral and balanced, even my art will be the subject of a more fair judgment.”

[71]

However, it is

important to emphasize that this assessment may have been the result of the

specific mood of the painter. To Corinth were bestowed outstanding honours

after his death: an exhibition at the National Gallery in Berlin, a series of

travelling exhibitions in Dresden, Chemnitz, Düsseldorf, Frankfurt, Leipzig,

Munich, Vienna, Hamburg, Bremen, Kassel, Wiesbaden, Cologne, Danzig/Gdansk and

Könisberg; the publication of the Autobiography

itself. It is the wife to give us a detailed account, with great emotion, of

the great retrospective exhibition of 1926 in Berlin; the National Gallery had

displayed the half-mast flags of the Republic, in front of them braziers are

burning, and Chancellor Luther intervenes at the inaugural ceremony, and points

in his speech to Corinth as an example to all Germans [72]. The Republic, which

Lovis Corinth had not loved, bows to him.

The writings of the wife and the son

Charlotte

Berend-Corinth (1880-1967), a young and beautiful emancipated woman, energetic

and resolute, orphan of a suicide father, madly in love with a much older and

always ill man, was a good painter and exhibited in her name, as Charlotte

Berend, in different aspects of Secession. As already mentioned, the husband

portrayed her in dozens and dozens of paintings.

|

| Fig. 7) A version of the Autobiography of 2017 produced by the on-demand publisher Hofenberg |

In 1937 she completed a touching collection of imaginary letters to her husband, My Life with Lovis Corinth (Mein Leben mit Lovis Corinth), but could not publish it: Corinth had been included in the list of Degenerate Art, and she was Jewish. It will be released in 1947, after the end of the war. In 1958 she published a second book, titled Lovis, and the same year the catalogue raisonné of the works of her husband. She lived the second half of her live in the US, but her archive is stored at the Academy of Fine Arts of Berlin [74].

The volume of

1948, which I consulted in a version of 1960, provides abundant information on

the birth of the Autobiography. We

read that Charlotte started the work in October 1925, after she had found some

notes organized in chaotic form, among the papers of her husband. There were some

well-organized notebooks. Corinth had, however, scrabbled the last part of his

autobiography (the one which we described as ‘third part’ in this blog) on the

left side of the same notebooks which he had already used on the right side as

a manuscript for the handbook "Learning

the painting" of 1908. The text was sometimes subject to extensive

corrections, sometimes repeated itself. The wife wanted to leave as much as

possible intact the original text of her husband, while the publisher would

have liked instead to put his hand on the text, to reconstruct the events

chronologically. [75]

The son Thomas has dedicated his entire life to the collection and publication of the critical edition of all the documentary material of the father: letters, memos, unused pages of writings, pages from memories of other painters, newspaper articles, and a rich collection of photos: 570 pages of documentation. What is striking is the almost complete lack of any interplay of Corinth with artists, personality or simple people, who were not German citizens. The visits in Italy and Switzerland had predominant purpose of rest. We are therefore in a purely national framework. Paradoxically, Thomas has lived in the United States.

NOTES

[24] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 149

[25] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, pp. 175-182

[26] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 186

[27] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 190

[28] Zimmermann, Michael F. - Lovis Corinth, quoted, p. 10

[29] Corinth, Lovis - Meine frühen Jahre, Hamburg, Claassen, 1954. Sections

of the text are available on the Internet. See:

http://books.google.de/books?id=97gpSmVuHQwC&pg=PP1&lpg=PP1&dq=Meine+fru%CC%88hen+Jahre+lovis+corinth&source=bl&ots=KOJTLahFrD&sig=8OuWhJH1jGfwtfS9sAbYb4G3BeA&hl=it&sa=X&ei=r2YwVInOHcXVatSAgrAJ&ved=0CFkQ6AEwBw#v=onepage&q=Meine%20fru%CC%88hen%20Jahre%20lovis%20corinth&f=false

e http://gutenberg.spiegel.de/buch/meine-fr-1494/1

[30] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 49

[31] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 78 e p. 225

[32] Berend-Corinth - Charlotte, Mein Leben, quoted , p. 64

[33] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 124

[34] Berend-Corinth, Charlotte -

Mein Leben, quoted, p. 74

[35] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 179

[36] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 149

[37] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 194

[38] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 199

[39] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, pp. 210-211

[40] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 200

[41] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 216

[42] Berend-Corinth - Charlotte, Mein Leben, Quoted, pp. 26, 35, 63

[43] Sauerlandt Max - Die Kunst der Letzten Dreißig Jahre,

Berlin, Rembrandt Verlag, 1935

[44] Le Correspondant, 25

novembre 1916, published in Maurice Denis, Théories, 1890-1910; du

symbolisme et de Gauguin vers un nouvel ordre classique, Rouart et Watelin,

Parigi, 1920 (See: https://archive.org/details/thories189019100deniuoft)

[45] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 152

[46] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 151

[47] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 163

[48] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 165

[49] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 167

[50] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 169

[51] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 170

[52] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 173

[53] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 188

[54] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 201

[55] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 204

[56] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 204-207

[57] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 190

[58] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 184

[59] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 190

[60] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 189

[61] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 191

[62] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 194

[63] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 198

[64] Uhr, Horst - Lovis Corinth, Berkeley, University of California

Press, 1990 (Si veda: http://publishing.cdlib.org/ucpressebooks/view?docId=ft1t1nb1gf;brand=ucpress)

[65] Uhr, Horst - Lovis Corinth, quoted, p. 227

[66] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 153

[67] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 154

[68] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 157

[69] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 158

[70] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 168

[71] Corinth, Lovis – Selbstbiographie, quoted, p. 209

[72] Berend-Corinth - Charlotte, Mein Leben, quoted pp.

21, 53 e ss., 65 e ss.

[73] Cultura tedesca a Firenze. Scrittrici e artiste tra Otto e Novecento, edited

by Maria Chiara Mocali, Claudia Vitale, Firenze, Le Lettere, pp. 285

[74] http://www.adk.de/de/archiv/archivbestand/bildende-kunst/index.htm?hg=bild&we_objectID=200&seachfor=.

[75] Berend-Corinth - Charlotte, Mein Leben, quoted pp. 32-33

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento